Church of St Peter, West Knighton. Grade 1, NGR: SY7324487623. Lead author: PS

The village is situated about 3 miles south east of Dorchester. It is recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Chenistetone’ which means ‘farm of the thanes’. The village stands on Palaeocene Reading Formation beds which are coarse sands and gravels devoid of fossils laid down 59 -56 million years ago. Clay from these beds was used in brick-making from 1734 onwards but the brickworks closed in 1939 when the site became uneconomic compared with bricks made from the Oxford Clay extracted from the Crook Hill Brick it at Chickerell (Perkins, J.W., Geology Explained in Dorset, p. 172, Pub. D. Charles Ltd (1977).

The church (1a, 1b), which stands on a mound above the road opposite Manor Farm on the edge of the village, was built in the 12th century, but only the east wall and part of the north wall of the nave remain. The base of the side walls of the chancel are also thought to date from the 12th century. In the 13th century the nave was extended, the chancel was rebuilt and a south aisle was added. A north porch was added in the 14th century and at a later date re-built with the same materials. The lower two stages of the tower were built in the 13th century and a third stage added in the 15th century. The church was restored in 1893. The architect was Thomas Hardy much more widely known as an author.

The exterior

The nave roof is of modern sheet metal design but the chancel is roofed with Purbeck limestone flagstones (8). The south chapel (20) and porch (12b) have some Purbeck flagstones at lower levels.

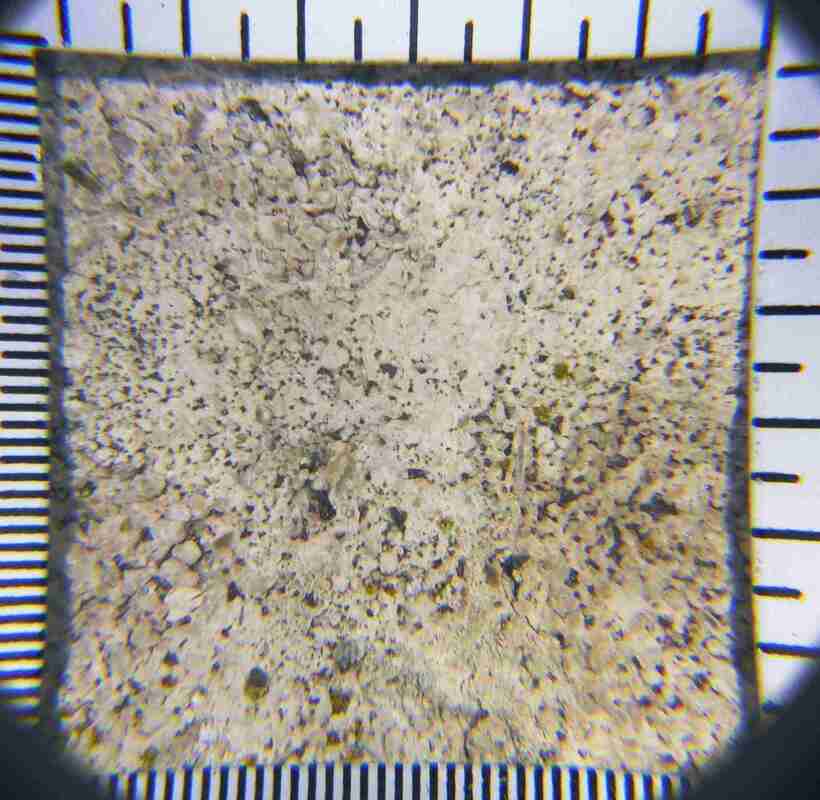

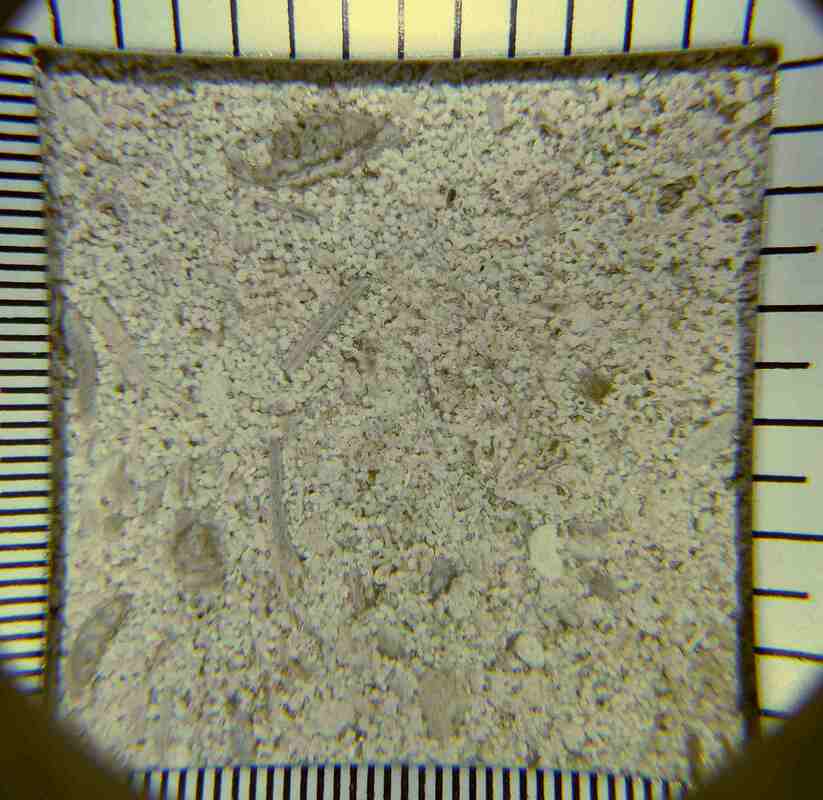

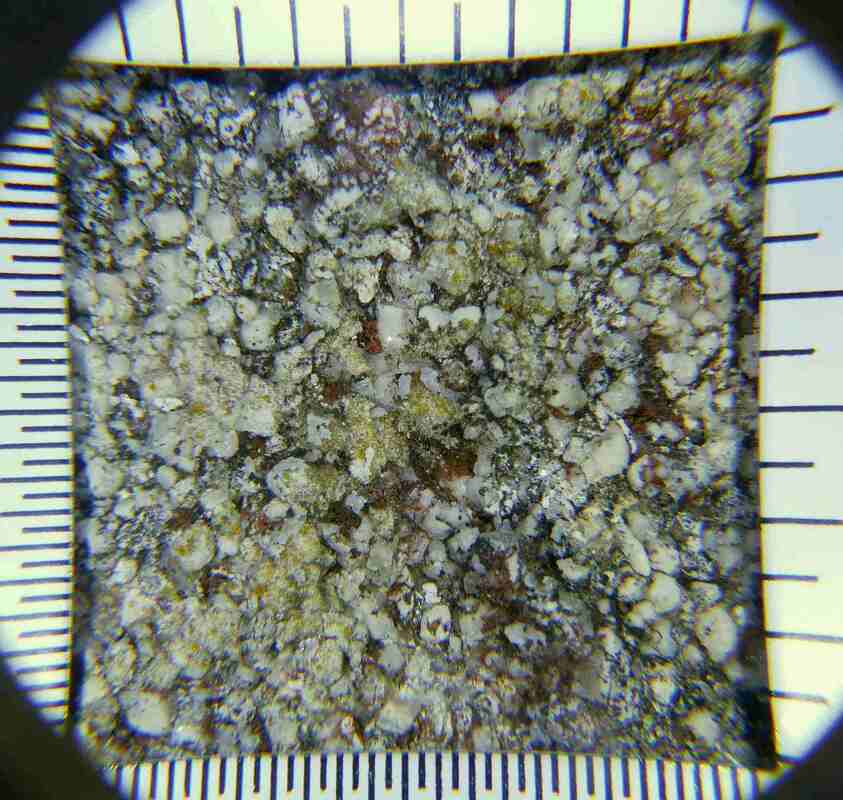

The stone used in the exterior walls are irregularly-sized, roughly shaped blocks without a finished surface often called ‘rubble stone’. The main building stone is Early Cretaceous, Purbeck Cypris Freestone, but a number of other types of stone have been incorporated into the exterior walls in smaller amounts.

The nave roof is of modern sheet metal design but the chancel is roofed with Purbeck limestone flagstones (8). The south chapel (20) and porch (12b) have some Purbeck flagstones at lower levels.

The stone used in the exterior walls are irregularly-sized, roughly shaped blocks without a finished surface often called ‘rubble stone’. The main building stone is Early Cretaceous, Purbeck Cypris Freestone, but a number of other types of stone have been incorporated into the exterior walls in smaller amounts.

The chancel

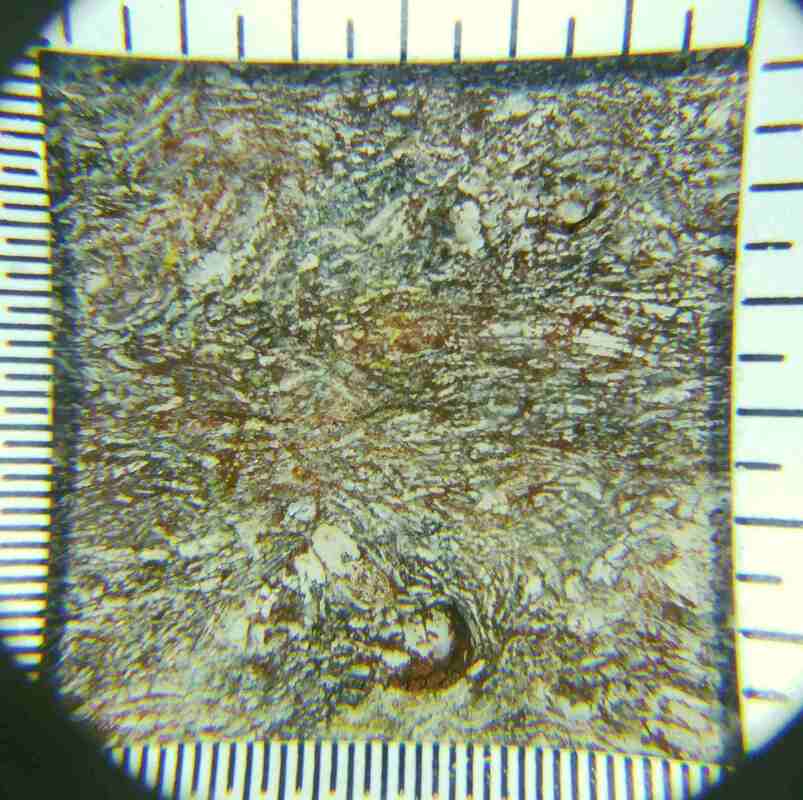

A typical example of the Cypris Freestone is the east wall of the chancel (3a, 3b).

A typical example of the Cypris Freestone is the east wall of the chancel (3a, 3b).

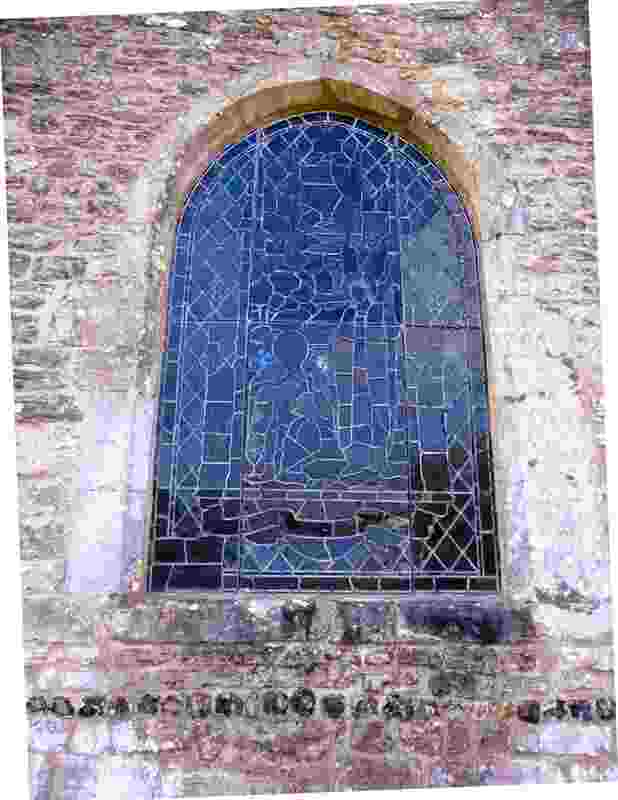

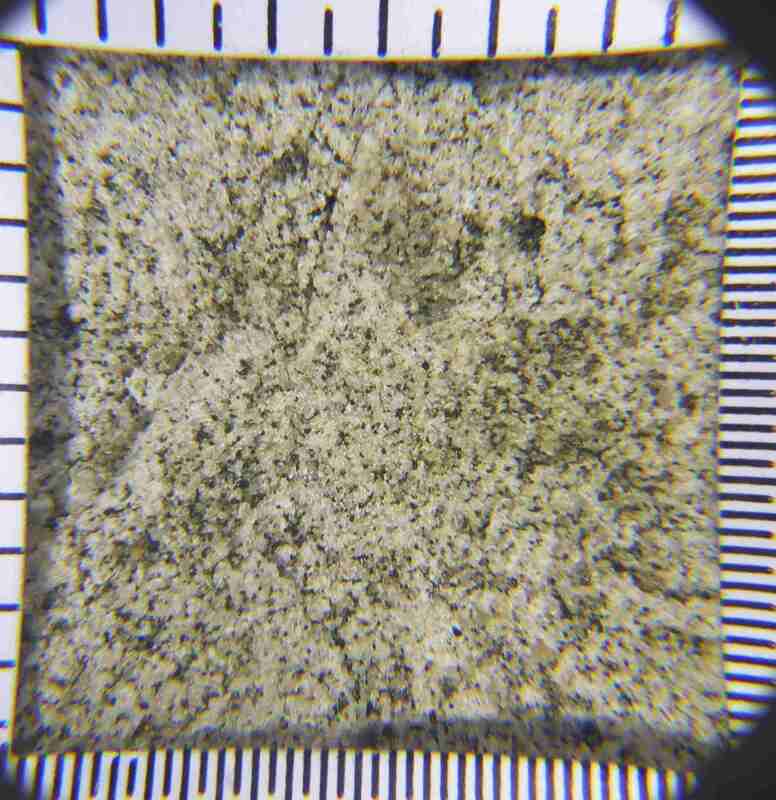

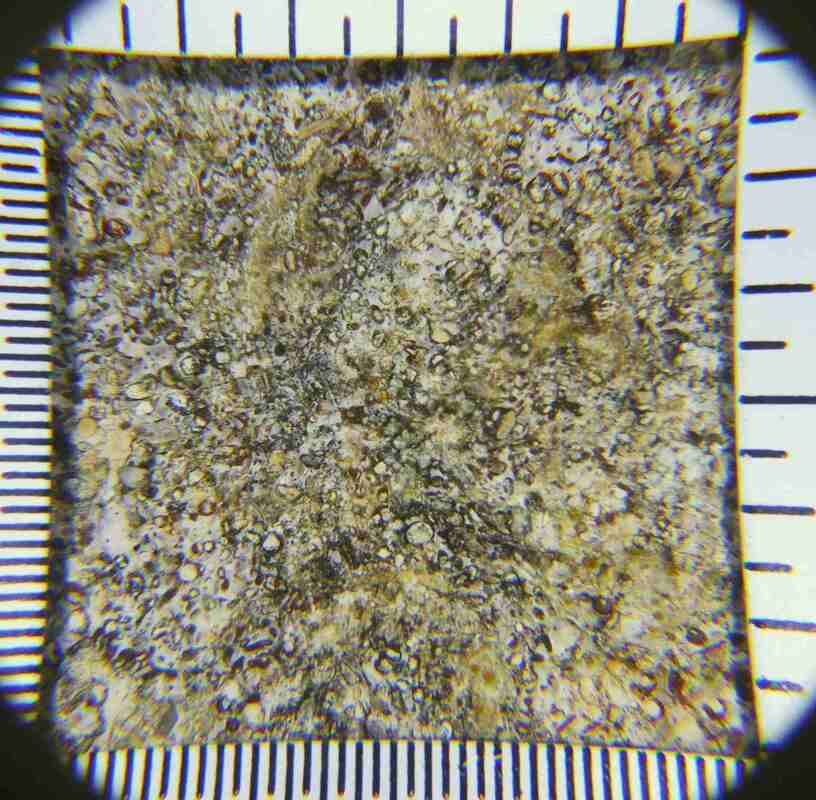

Besides Cypris Freestone there are blocks of Portland limestone particularly the quoins (4a, 4b); the east window is also Portland limestone (5a, 5b).

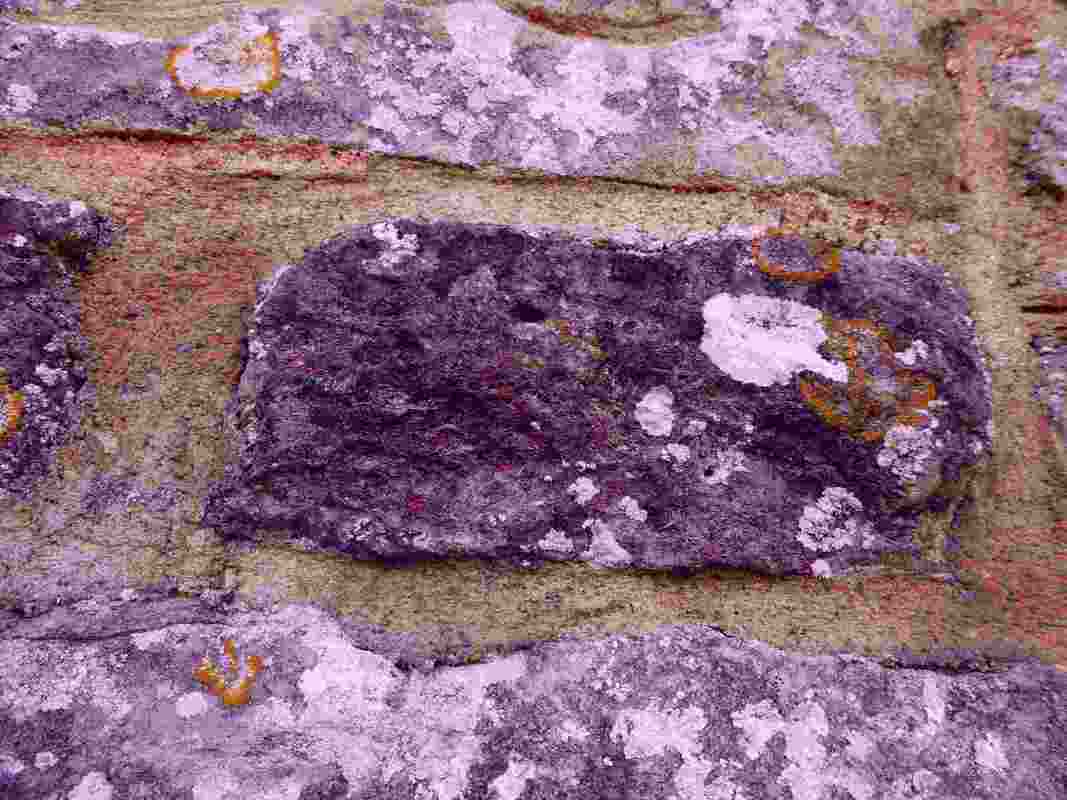

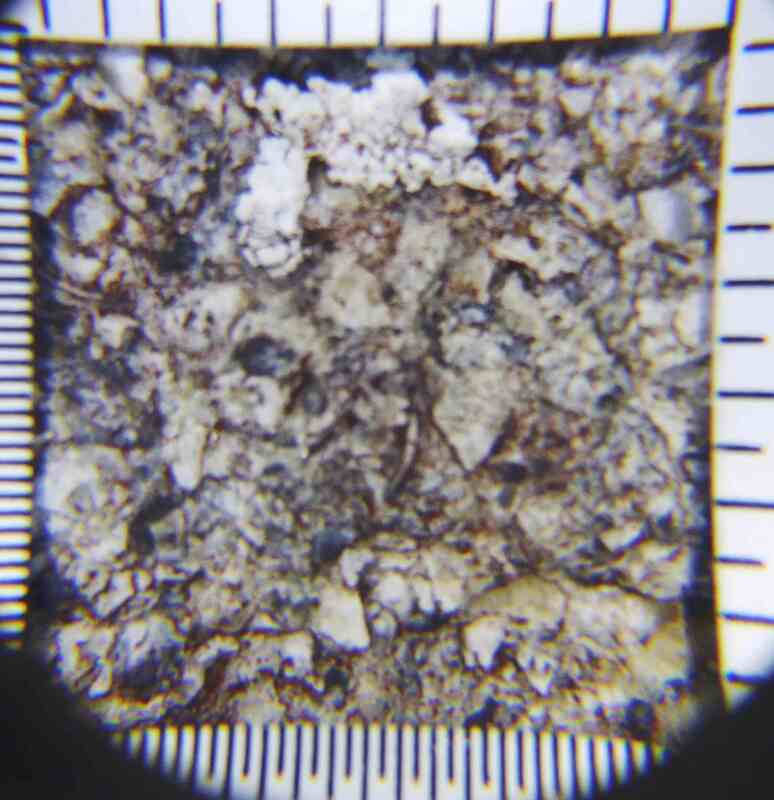

There are also blocks of Purbeck shell brash limestone, not individually identified but probably Upper Purbeck Burr (6a, 6b). The blocks look dark red as they are covered by red algae.

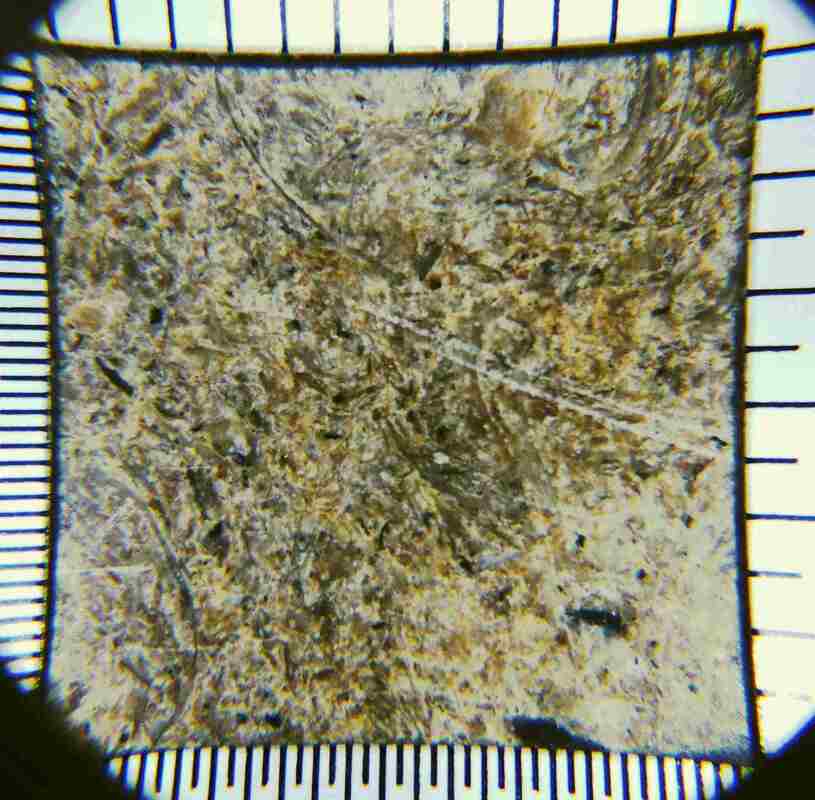

Blocks of Upper Greensand (7a, 7b), dark iron-rich Heathstone, another coarse sandstone, and tile have also been identified. A row of Flints runs just below the east window (7a).

The north wall (8) has a similar mix of stone but in addition there is a block of Chalk (9) and several blocks of coarse sandstone which has not been identified (10a, 10b) but may be from the Reading Beds.

The small priest’s doorway and lancet window are both Portland limestone. A vestry in brick has been built against the south wall (11a). The window is Portland limestone (11b)

The nave and porch

The north wall of the nave faces the road with the porch centrally placed. The walls were rebuilt in the 17th century with existing materials and are predominantly Cypris Freestone. In the wall on the eastern side of the porch, adjacent to the remnants of a 12th century buttress, is a carved plaque which reads ‘IOHN BOW 1.J.76.’ (12). It is Portland limestone. To the left and right of the porch are 15th century windows in Corallian limestone (13a, 13b, 13c).

The north wall of the nave faces the road with the porch centrally placed. The walls were rebuilt in the 17th century with existing materials and are predominantly Cypris Freestone. In the wall on the eastern side of the porch, adjacent to the remnants of a 12th century buttress, is a carved plaque which reads ‘IOHN BOW 1.J.76.’ (12). It is Portland limestone. To the left and right of the porch are 15th century windows in Corallian limestone (13a, 13b, 13c).

Other than two Heathstone blocks in the east wall (14), the walls of the porch are Cypris Freestone. The sides of the outer doorway are Portland limestone but the arch above is Cypris Freestone (15). The roof is tiled except for two rows of Purbeck limestone flags (15).

|

The south side of the church has a complex history. In the 13th century a south aisle was built which stretched the length of the nave. Only the west end of this wall, where it meets the tower, remains. In the 16th century the south wall was moved to widen the south aisle and a chapel (see below) was incorporated at the east end. In the 18th century the south aisle was demolished but the chapel was retained. The two redundant arches of the south arcade were filled in but are still visible on the exterior (16). The wall is now part rendered and the rest is Cypris Freestone. The window, presumably inserted at this time, is Portland limestone.

|

The tower (17a, 17b)

Like the rest of the walls the tower is mainly built of rubble Cypris Freestone with a scattering of other stone such as flint. There are also some blocks of Purbeck Marble in the north-west wall of the nave and the north and west walls of the tower (18a, 18b). On the east wall can be seen the line of the old nave roof (17b).

Like the rest of the walls the tower is mainly built of rubble Cypris Freestone with a scattering of other stone such as flint. There are also some blocks of Purbeck Marble in the north-west wall of the nave and the north and west walls of the tower (18a, 18b). On the east wall can be seen the line of the old nave roof (17b).

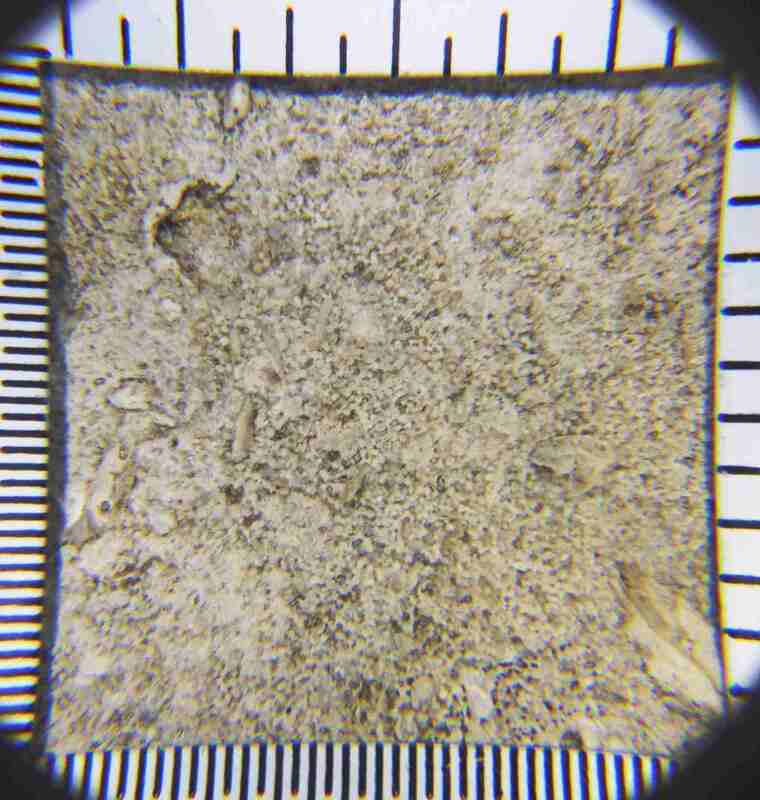

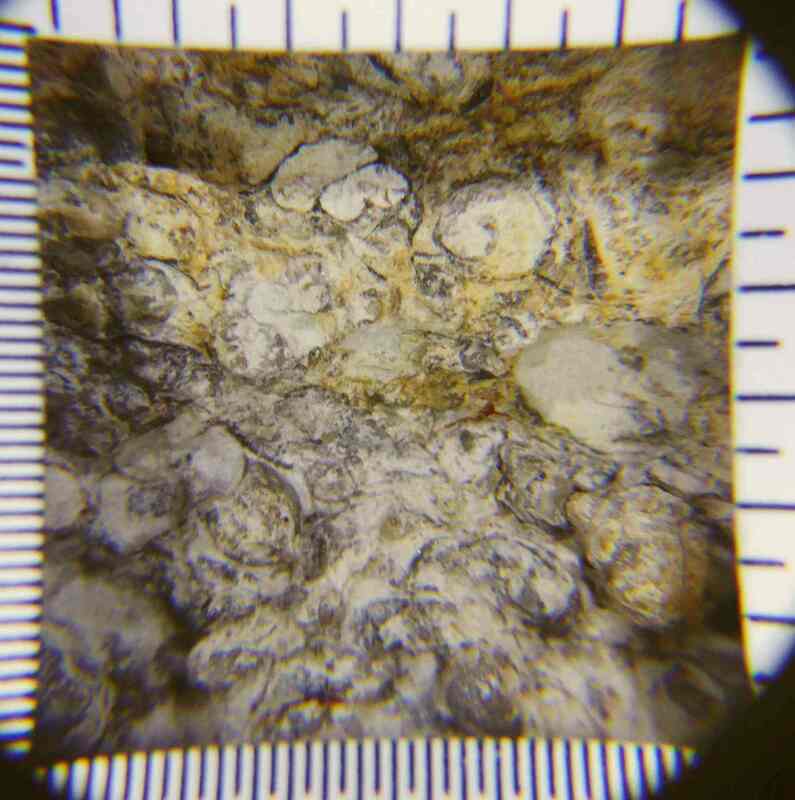

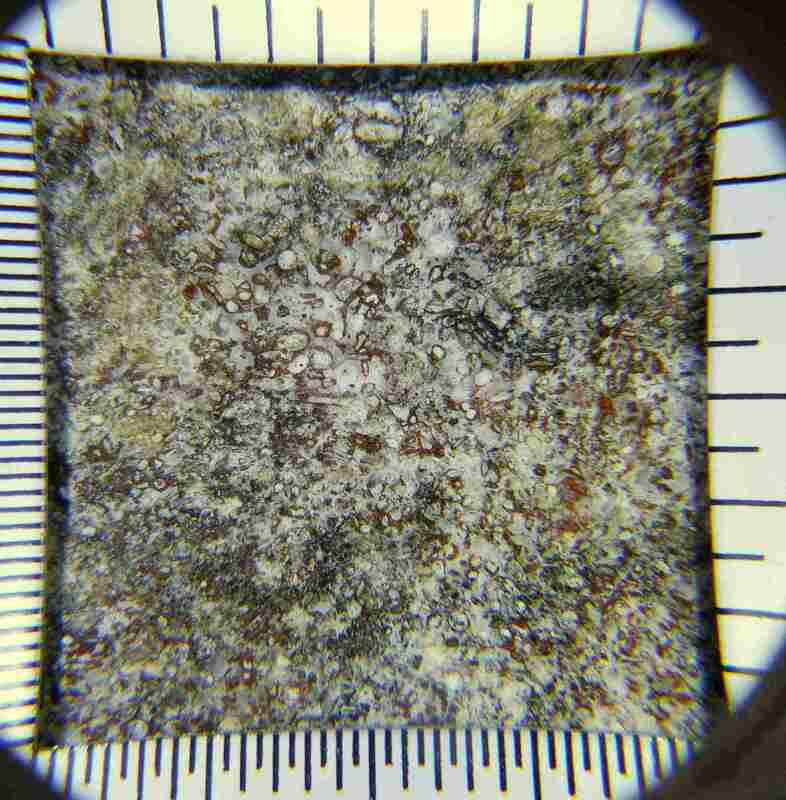

The small lancet window (19a) in the west wall is described as ‘restored’ in the RCHME description (no date given). It is made up of two types of stone (19b), neither positively identified. One is oolitic (19c); the other is not oolitic and is similar to Doulting Stone (19d). Each side of the apex of the lancet window is a block of Purbeck Marble (partly visible in 19a).

The south chapel (St George’s Chapel)

The roof has Purbeck slabs on the lower part but the apex it clad in red tiles (20). The 18th century west wall is rendered with knapped flint and mortar (20). A 16th century Portland limestone window has been inserted.

The roof has Purbeck slabs on the lower part but the apex it clad in red tiles (20). The 18th century west wall is rendered with knapped flint and mortar (20). A 16th century Portland limestone window has been inserted.

The south wall (21a) and part of the east wall of the chapel (22) date from the 16th century. The walls are mainly Cypris Freestone but there are some blocks of Heathstone and an occasional Flint scattered in the wall (21b).

Part of the east wall is 13th century; the remainder is 12th century. A small 13th century lancet window of Portland limestone marks the boundary between the two sides (22), but the 19th century vestry now obscures all but a small part of the 12th century part. Both are Cypris Freestone with occasional Flints and Heathstone.

The interior (23)

Much of the flooring is Purbeck Limestone, probably Purbeck Grub (24a, 24b).The walls are plastered.

Much of the flooring is Purbeck Limestone, probably Purbeck Grub (24a, 24b).The walls are plastered.

A Ham Hill Stone arcade, coated in whitewash or plaster, is built across the south chapel (25). The western two arches of the arcade now form part of the south wall of the nave. the chancel arch (26), originally 13th century, has been re-built. It is also Ham Hill Stone.

The font bowl of Ham Hill Stone (27) dates to the late 12th century but the stem and the base, both also Ham Hill Stone, and the four Purbeck Marble colonettes belong to the 19th century.

References

1) An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 2, pp. 135-140. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2/pp135-140

2) Hill M., Newman J., Pevsner N. (2018), The Buildings of England, Dorset, Yale U. Press, p.636

1) An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Dorset, Volume 2, pp. 135-140. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2/pp135-140

2) Hill M., Newman J., Pevsner N. (2018), The Buildings of England, Dorset, Yale U. Press, p.636