St. Bartholomew’s Church, Shapwick

ST93656 01675, 50.8146 -2.0914. Lead authors PB and JT.

First built in the 12th century, using Heathstone and Flint that could be found in the widespread valley gravels, the church has been altered in the 14th, 15th, 16th and 19th centuries. Only the north wall of the nave remains of the 12th century church, and on the outside the use of Heathstone and flint is random, whereas later work is more ordered. The 14th century west tower and south wall, including the south porch, have Heathstone and Flint banded, the Heathstone being used in large blocks for the quoins. Although mainly flint, the valley gravels include blocks of Heathstone of different sizes, including large boulders, though it is possible that some fresh blocks could have been quarried from the Tertiary high ground south of Sturminster Marshall. The c hurch has clay tiled roof with eight courses of Purbeck stone at the verge.

The original 12th century north wall of the nave has been raised, probably at the same time as the tower was added in the 14th century, first with a line of coffin lids, and then with mixed blocks of the Heathstone and Purbeck limestones.

In the 15th century a north chapel was added, using flint, Heathstone and Purbeck stone banded, with the occasional block of Upper Greensand. The upper part of this wall was raised in the 16th century with flint and ‘jumpers’ (occasional blocks) of heathstone, Purbeck limestone and Upper Greensand.

In the 15th century a north chapel was added, using flint, Heathstone and Purbeck stone banded, with the occasional block of Upper Greensand. The upper part of this wall was raised in the 16th century with flint and ‘jumpers’ (occasional blocks) of heathstone, Purbeck limestone and Upper Greensand.

1. 12th C. North Nave random rubble wall.

2. Late 13th into 14th C. Tower - banded Flint & Heathstone walls.

3. A row of broken 14th C. coffin lids mark 14th C. Nave heightening.

4. Flint & squared block Heathstone of N. Chapel banding as in Tower.

5. 16th C. additional Porched wall to enclose original 12th C. doorway.

6. 15th C. N. Chapel heightening with large Upper Greensand blocks & Flint.

7. 15th C. Oolitic Corallian Limestone & 19th C. Bath Stone re-build of mullion & sill.

8. Late 15th C. Tower completed with coursed Heathstone & Upper Greensand quoins.

9. Buttress 14th C. Purbeck Burr.

10. Purbeck limestone window - Cypris stone textured.

11. Buttress 14th C. Wardour Lower Building Stone with Heathstone.

12. 19th C. Ham Hill Stone & Flint buttress.

13. Upper Greensand full window - 15th C.

2. Late 13th into 14th C. Tower - banded Flint & Heathstone walls.

3. A row of broken 14th C. coffin lids mark 14th C. Nave heightening.

4. Flint & squared block Heathstone of N. Chapel banding as in Tower.

5. 16th C. additional Porched wall to enclose original 12th C. doorway.

6. 15th C. N. Chapel heightening with large Upper Greensand blocks & Flint.

7. 15th C. Oolitic Corallian Limestone & 19th C. Bath Stone re-build of mullion & sill.

8. Late 15th C. Tower completed with coursed Heathstone & Upper Greensand quoins.

9. Buttress 14th C. Purbeck Burr.

10. Purbeck limestone window - Cypris stone textured.

11. Buttress 14th C. Wardour Lower Building Stone with Heathstone.

12. 19th C. Ham Hill Stone & Flint buttress.

13. Upper Greensand full window - 15th C.

In the 16th century the east wall of the north chapel was replaced, with the addition of a north-east corner buttress of Wardour Lower Building Stone – a sandy limestone. The east wall is banded using flint, Heathstone, Upper Greensand, a cream oolite believed to be the Corallian from Marnhull, shelly Purbeck limestone and the Wardour sandy limestone. In the same century a north porch was formed by the addition of a western wall to enclose the existing 12th century north door – a Purbeck Marble cross being included in the wall.

The Hussey tomb in the north chapel has been built of Corallian limestone, from the Hussey land in Marnhull. The Husseys, spelt variously, have been numerous in Dorset since the time of the Domesday Book, and also lived in colonial America. Their Norman and Tudor connections, followed by strong royalist persuasion, brought no great riches and the church employed many of their Oxbridge graduates across the country. Shapwick Manor, its church and village came to the family by marriage in the 1370’s, and remained their property until being sold in the 1640’s to Colonel William Wake, whose son became Archbishop of Canterbury. Hence the name Bishop’s Court for the manor house. [In 1773 the estate was sold again to Henry Bankes and became part of the Kingston Lacy estate now owned by the National Trust.]

The only 18th century work marked on the Royal Commission for Historical Monuments website (RCHME, found under British History Online) floor plan is the base of the chancel arch. The supporting pillar on the north seems similar stone – a grey oolite - to the 12th century north nave arch next to it, but the upper arch is Ham Hill Stone, and must be 19th century. The southern supporting pillar is similarly grey, but looks more like the Purbeck Burr. The two brick buttresses on the north wall of the north chapel are also marked as 18th century. As this could have been under the ownership of the Bankes estate, stone from the Isle of Purbeck would be readily available.

Finally, after 1850, the chancel was rebuilt using the same mixture of Flint, Heathstone, Purbeck limestone and Upper Greensand, but arranged as a mainly flint wall with the other stones as occasional ‘jumpers’. This is typically 19th century masons’ work. At the same time buttresses were added to the north and south nave walls using Ham Hill Stone with flint.

The windows and doorways, as seen from outside, are of various dates. The earliest are in the south wall of the nave, all 14th century. These are all of Upper Greensand, with a very few higher blocks in each window surround that could be the Wardour sandy limestone. In the tower, the high slit window is of Heathstone, but the lower main window is dated 15th century and appears to have weathering characteristics like those of the Purbeck Cypris Freestones, but of a somewhat darker colour. Comparison with the windows in Cerne Abbas, where we know the stone is Cypris Freestone from Poxwell quarry, make this identification probably correct. The darker colour may be simply due to different weathering or damp, being next to the river Stour.

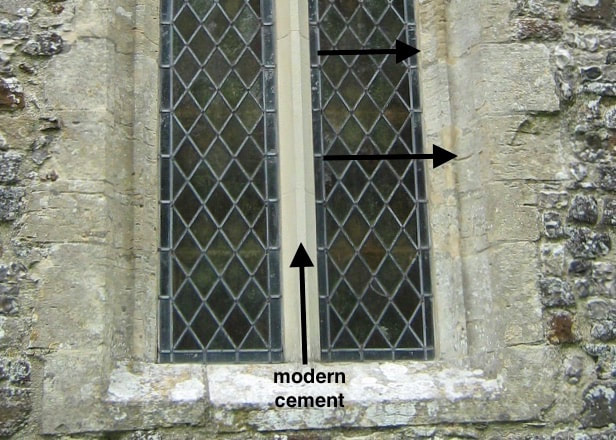

The window west of the north porch is the same date as the two windows in the north wall of the north chapel – 15th century or possibly 16th century. This one in the nave wall is of cream oolite that we now believe (after historical research) to be Corallian Todber Freestone from the Hussey lands in Marnhull, with a recent repair of the mullions and cill of Bath Stone with shell bands. In the north chapel the window west of the vestry door is of Ham Hill Stone with mullions of Bath Stone as in the previous window. A rectangular opening below has been blocked with slate, surrounded by Heathstone and Upper Greensand. The North porch outer archway (16th century) is of heathstone, while the inner archway, dated 12th century, although covered in mould, appears to be Upper Greensand. The window east of the vestry door is of the same cream oolite as before, weathering noticeably. The vestry doorway is 19th century Ham Hill Stone.

The window facing east in the north chapel is dated 16th century and has an upright on the south side of Heathstone, and on the north side of cream oolite (‘Marnhull stone’), with mullions that look like concrete.

Finally, the windows in the chancel and the west wall of the south porch are all Ham Hill Stone – 19th century.

For the church structurally, it has been a largely frugal existence, making the most of the Flint and Heathstone available on a flood plain over the Chalk. Dimensional building stone had to brought in from elsewhere, including Hussey land in Marnhull. Not until the 1860’s fervour for rebuilding was the masonry of the very highest order, here in the 1878 chancel rebuild.

(JT & PJB 12.10.2017) Text JT and photos PB, except where stated otherwise. October 2017.

The Hussey tomb in the north chapel has been built of Corallian limestone, from the Hussey land in Marnhull. The Husseys, spelt variously, have been numerous in Dorset since the time of the Domesday Book, and also lived in colonial America. Their Norman and Tudor connections, followed by strong royalist persuasion, brought no great riches and the church employed many of their Oxbridge graduates across the country. Shapwick Manor, its church and village came to the family by marriage in the 1370’s, and remained their property until being sold in the 1640’s to Colonel William Wake, whose son became Archbishop of Canterbury. Hence the name Bishop’s Court for the manor house. [In 1773 the estate was sold again to Henry Bankes and became part of the Kingston Lacy estate now owned by the National Trust.]

The only 18th century work marked on the Royal Commission for Historical Monuments website (RCHME, found under British History Online) floor plan is the base of the chancel arch. The supporting pillar on the north seems similar stone – a grey oolite - to the 12th century north nave arch next to it, but the upper arch is Ham Hill Stone, and must be 19th century. The southern supporting pillar is similarly grey, but looks more like the Purbeck Burr. The two brick buttresses on the north wall of the north chapel are also marked as 18th century. As this could have been under the ownership of the Bankes estate, stone from the Isle of Purbeck would be readily available.

Finally, after 1850, the chancel was rebuilt using the same mixture of Flint, Heathstone, Purbeck limestone and Upper Greensand, but arranged as a mainly flint wall with the other stones as occasional ‘jumpers’. This is typically 19th century masons’ work. At the same time buttresses were added to the north and south nave walls using Ham Hill Stone with flint.

The windows and doorways, as seen from outside, are of various dates. The earliest are in the south wall of the nave, all 14th century. These are all of Upper Greensand, with a very few higher blocks in each window surround that could be the Wardour sandy limestone. In the tower, the high slit window is of Heathstone, but the lower main window is dated 15th century and appears to have weathering characteristics like those of the Purbeck Cypris Freestones, but of a somewhat darker colour. Comparison with the windows in Cerne Abbas, where we know the stone is Cypris Freestone from Poxwell quarry, make this identification probably correct. The darker colour may be simply due to different weathering or damp, being next to the river Stour.

The window west of the north porch is the same date as the two windows in the north wall of the north chapel – 15th century or possibly 16th century. This one in the nave wall is of cream oolite that we now believe (after historical research) to be Corallian Todber Freestone from the Hussey lands in Marnhull, with a recent repair of the mullions and cill of Bath Stone with shell bands. In the north chapel the window west of the vestry door is of Ham Hill Stone with mullions of Bath Stone as in the previous window. A rectangular opening below has been blocked with slate, surrounded by Heathstone and Upper Greensand. The North porch outer archway (16th century) is of heathstone, while the inner archway, dated 12th century, although covered in mould, appears to be Upper Greensand. The window east of the vestry door is of the same cream oolite as before, weathering noticeably. The vestry doorway is 19th century Ham Hill Stone.

The window facing east in the north chapel is dated 16th century and has an upright on the south side of Heathstone, and on the north side of cream oolite (‘Marnhull stone’), with mullions that look like concrete.

Finally, the windows in the chancel and the west wall of the south porch are all Ham Hill Stone – 19th century.

For the church structurally, it has been a largely frugal existence, making the most of the Flint and Heathstone available on a flood plain over the Chalk. Dimensional building stone had to brought in from elsewhere, including Hussey land in Marnhull. Not until the 1860’s fervour for rebuilding was the masonry of the very highest order, here in the 1878 chancel rebuild.

(JT & PJB 12.10.2017) Text JT and photos PB, except where stated otherwise. October 2017.

Exterior Stone Detail

A. 16th C. banded squared-off Heathstone rubble; in double or triple flint courses, replicates the 13th/14th C. original West Tower walling at a reduced scale. West of the right hand brick buttress the first five bands of Heathstone appear intact but eastwards only the lower two Heathstone bands remain in context. Although not recorded, some of this Chapel space was accessed from the nave by way of the two capacious north nave stone arches. The eastern arch is considered 16th C. (British Listed Buildings.) but the western arch to be 12th C. - so in monastic times a covered building, of now indeterminate size stood here and probably to the height of the 5th red sandstone band.

B.This one stage buttress is all of Wardour Lower Building Stone, un-weathered but well lichened and was built to retain the known 15th C extension & rebuilding of this the Priory or North Chapel RCHME p. 57.

C. Above the porch, (see the cream coloured decorative quatrefoil added above) evidence for a once lower gable-end structure.

D. The heightening and lengthening of the north Chapel walls, early in the 16th C., stands out more than any other historic progression. Predominantly held together by Upper Greensand, in a variety of large sizes and colour tones, may suggest they were recycled from another building, rather than new from a quarry? Earlier dimensional Upper Greensand is seen in the 16th C. eastern extension and at the blocked opening below window G.

E. Two centuries later, the north Chapel wall probably began to de-stabilise or bulge and these two English bond brick buttresses were built into this wall.

F. This North Dorset Corallian oolitic limestone window, frame and mullions, is dated within the15th C. but it may have been 16th C. re-cycled here from the original East wall. This north Chapel may well have been, post-Reformation, a private chapel to the Hussey family until about 1640.

G. It has been proposed that this 15th C. Ham Hill Stone window was the original Chapel’s east window before the extension of the early 16th C. But if so - where did window F come from? Window G mullions have needed replacement; as was also required in the north nave window No 7 (see above) and using the same shell banded Bath Stone. This window is centre elevated above a seemingly never glazed opening but is recorded as a 'light’.

H. A Welsh slate panel now fills the opening recorded as a “light” but this opening was built off centre to the interior recessed and expensively ornamented 15th C. wall and so, which came first?

I. Against the still immaculate but lichened early 16th C. Wardour Lower Building Stone buttress at eye level, are a group of three clean blocks of that same stone.

J. The green-toned stone in the rounded 16th C. porch arch is now a crumbly block of this same fine-grained sandy limestone.

K.The black arrowed wall plate of a fine-grained cream coloured stone is either this same Wardour Lower Building Stone or a north Dorset Corallian oolite. As the wall plate, where visible, is now mostly well weathered, most probably it is the latter but with possible 19th C. Ham Hill Stone repairs?

L. The 19th C. Ham Hill stone doorway.

M. Middle Purbeck limestone roofing tiles.

B.This one stage buttress is all of Wardour Lower Building Stone, un-weathered but well lichened and was built to retain the known 15th C extension & rebuilding of this the Priory or North Chapel RCHME p. 57.

C. Above the porch, (see the cream coloured decorative quatrefoil added above) evidence for a once lower gable-end structure.

D. The heightening and lengthening of the north Chapel walls, early in the 16th C., stands out more than any other historic progression. Predominantly held together by Upper Greensand, in a variety of large sizes and colour tones, may suggest they were recycled from another building, rather than new from a quarry? Earlier dimensional Upper Greensand is seen in the 16th C. eastern extension and at the blocked opening below window G.

E. Two centuries later, the north Chapel wall probably began to de-stabilise or bulge and these two English bond brick buttresses were built into this wall.

F. This North Dorset Corallian oolitic limestone window, frame and mullions, is dated within the15th C. but it may have been 16th C. re-cycled here from the original East wall. This north Chapel may well have been, post-Reformation, a private chapel to the Hussey family until about 1640.

G. It has been proposed that this 15th C. Ham Hill Stone window was the original Chapel’s east window before the extension of the early 16th C. But if so - where did window F come from? Window G mullions have needed replacement; as was also required in the north nave window No 7 (see above) and using the same shell banded Bath Stone. This window is centre elevated above a seemingly never glazed opening but is recorded as a 'light’.

H. A Welsh slate panel now fills the opening recorded as a “light” but this opening was built off centre to the interior recessed and expensively ornamented 15th C. wall and so, which came first?

I. Against the still immaculate but lichened early 16th C. Wardour Lower Building Stone buttress at eye level, are a group of three clean blocks of that same stone.

J. The green-toned stone in the rounded 16th C. porch arch is now a crumbly block of this same fine-grained sandy limestone.

K.The black arrowed wall plate of a fine-grained cream coloured stone is either this same Wardour Lower Building Stone or a north Dorset Corallian oolite. As the wall plate, where visible, is now mostly well weathered, most probably it is the latter but with possible 19th C. Ham Hill Stone repairs?

L. The 19th C. Ham Hill stone doorway.

M. Middle Purbeck limestone roofing tiles.

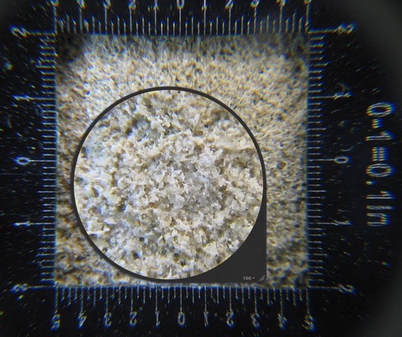

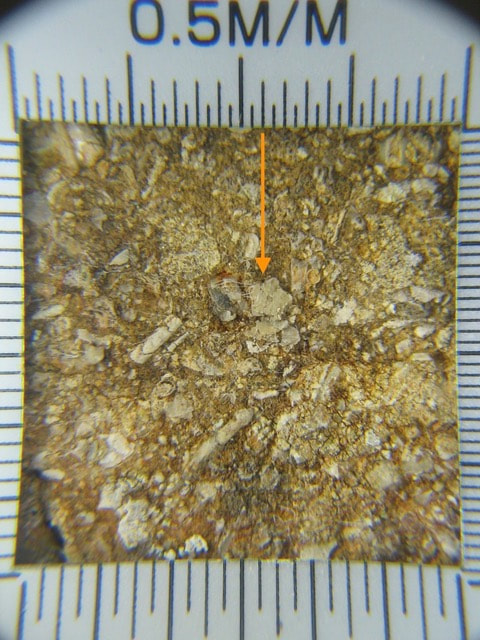

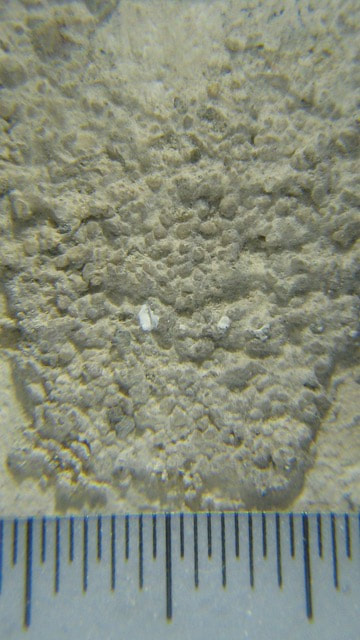

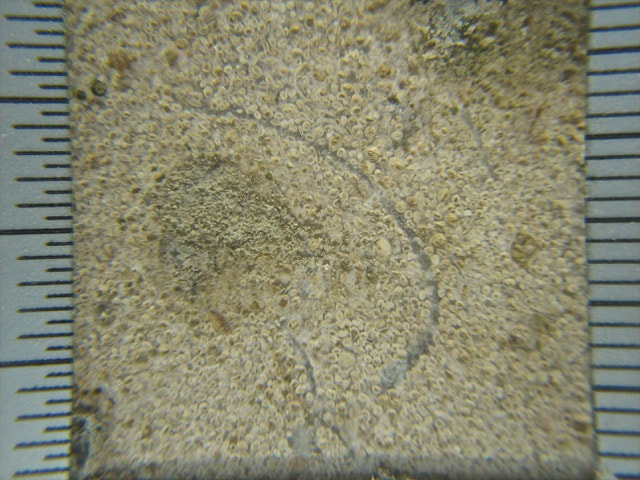

Letter I above: Clean Wardour Lower Building Stone, limestone with hint of bedding, against to left the lichened buttress of this stone B, above. A high magnification hand lens view reveals very fine angular quartz sand grains in these three examples.

|

|

Darker dots are ooid cavities surrounded by remaining cement in both these very well matching 20mm x 20mm close ups.

|

a. Wardour Lower Building Stone d. Ham Hill stone.

b. Upper Greensand. e. Flint. c. Purbeck Burr (aka Broken Shell Limestone) f. Middle Purbeck |

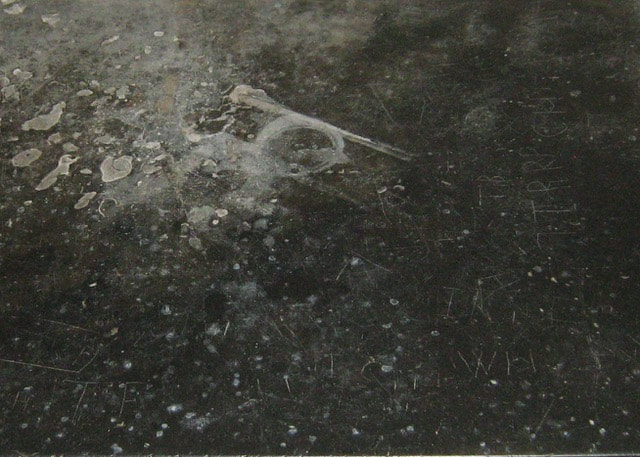

All building stones on the key to the left, and more, are to be found here widely spread in the walls of the east end. Every cross is of Ham Hill Stone.

|

Interior Stone detail

|

|

|

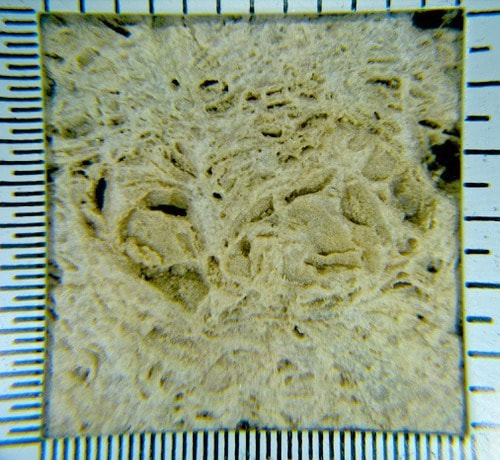

Shapwick Manor and St. Bartholomew were in the hands of the Hussey family until almost the mid- 17th C. There is every reason to believe that all three stones could be matched more definitely with particular source areas. The Marnhull Stone from Whiteway Hill is markedly dark shell-textured and fine-grained and these beds today still produce any size of dimension stone that could be wished for. Todber stone is often completely shell-free, is generally creamier than the light grey of Whiteway and has a coarser grain size and texture. That only the proven ‘good building stone’ was chosen by rural Royalist landowners for dimensional and moulded stone seems evident even at Shapwick, where it has remained effectively for centuries amongst flint and rubble. A fourth oolitic limestone comes up next in the middle upright between face shielded slabs of the table tomb.

|

The late 15th C. Purbeck Marble elliptical headed recess with rose-traceried spandrels has no pillars. It is offset to the earlier same century window and is perfectly shaped to have originally had just an Easter sepulchre shelf rather than a tomb or sedilla set across the recess.

(see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Easter_Sepulchre#/media/File:Sedilla.JPG) Hutchins’ 1st edition of 1774 refers to a table-top tomb ‘reportedly' being seen in the chancel, “with three blank shields in as many quarterings.” Editors to his third edition of 1868 say it was at their time in the north-east corner of the Priory chapel and with two shields, so it was likely moved to its present position in the 1878 St Bartholomew’s restoration. That this off-set decorative recess feature was originally an Easter Sepulchre, with no tomb, still doesn't explain the presence of the slate blocked opening on the outside wall. The slate covered opening, recorded generally as a “light” and the early 15th C. window above it are incongruous in themselves but they must pre-date the internal alterations of the Victorian restoration in 1868. It is thought that this unglazed “light’ was a medieval hagioscope - a leper’s squint; because it is set square to where the altar would have been in the Priory Chapel prior to the 16th C. extension of this chapel to the East.

|

The polished black tomb top slab is Blue Lias, a soft limestone from Somerset quarries, many still working east to west at Keinton Mandeville, Charlton Adam, and Somerton. But for

the central vertical panel of oolitic limestone separating the two shielded facing slabs, the tomb is all of Wardour Lower Building Sand. The central Oolitic limestone panel is a perfect match for today’s dimensional stone from Whiteway Quarry, Marnhull. “The massive marble slab” of written records is really Blue Lias because; weathering out of some thin bedding and trace fossils, along with personal initials of local miscreants would not be seen in the Belgian Black marble. Extended Hussey 17th C. family members were from Charlton Adam on the Blue Lias and table top tombs in a church are always a statement of eminence. So it’s most probable that this tomb was built earlier for the family rather than for the last ever born Hussey of Shapwick who’d by then held only the title. His grandmother and extended family inherited the manor house and all lands from 1604. The tomb and his wife’s elaborate wall memorial are also not made of the same stone.

|

,The memorial to the third and last Thomas Hussey of Shapwick and Tomson, once gloriously painted and likely not restored following the sale of the manor to another leading Royalist under Charles I a few years later. The memorial was gold leaf-inscribed and dated 1640 in Latin by his wife Eleanor, nee Morton of Milborne St Andrew's (John Hutchins, Shapwick.) The stone is all north Dorset Corallian oolitic limestone and much of it hand-tooled sculpture. One of the two shields on the table- top tomb is recorded as being of Hussey, the other of Morton. Eleanor’s tribute includes a wish to be buried with her husband but one of two in some ways incorrect Hutchins pedigrees holding her name, record a second marriage, so she’s likely buried elsewhere. Interestingly, the 4” median vertical panel today separating the two table tomb shields looks the same as the corner quoins in both size and colour but the stone is north Dorset ooidal limestone from somewhere not far from that used in the wall memorial. So the 1639 date for the tomb may refer to only modifications to the table tomb front panel(s). The almost local ooidal median panel may have been a modification or repair to the Wardour stone. (see also below.) The hand tooled reverse to the Hussey crest, currently awaiting repair, reveals superficial ooids typical of most north Dorset ooidal dimensional stones.

Central panel on the table top tomb memorial to 18th C. Thomas Hussey III. 20mm x 20mm close ups

|

|

|