Purbeck Marble (Lead Author: Pete Bath)

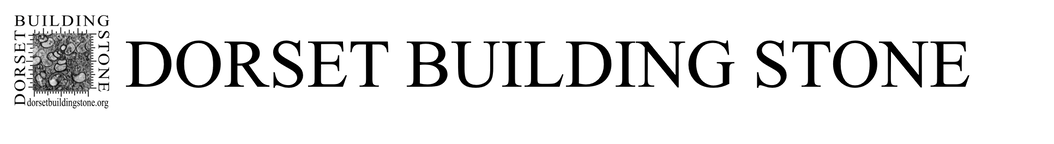

The Purbeck Group comprises the Lulworth Formation (three Members) overlain by the Durlston Formation (two Members). The Purbeck Marble occurs within the upper member of the Durlston Fm, the Peveril Point Member (Early Cretaceous, Berriasian), a little above the Broken Shell Limestone (qv). The Purbeck Limestone Group was deposited over a period of some 6 million years (146-140my).

|

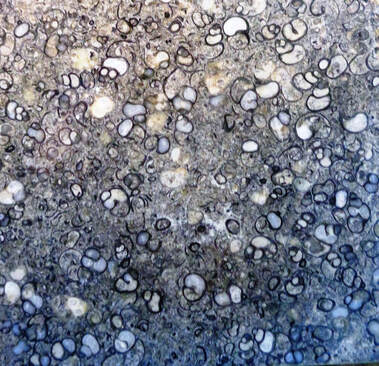

Purbeck Marble is a brackish/freshwater Viviparus gastropod limestone, quarried since Roman Times between Peveril Point, Swanage and Worbarrow Bay from the Upper Purbeck Durlston Formation. The thin beds of this stone, are usually of less than 12” (.3 m) in thickness but rarely as much as 1.00 m or more and these three beds are often varied in dominant colour upwards from grey to green and then to blue - when quarried. However, after exposure to sunlight and fresh air - the colour of this stone may change. ( see above) Bed thickness alone has limited how this stone could be used but given its shallow depth along its considerable outcrop, accessibility has not been too problematic.

Although adits have been opened southwards into the Purbeck limestones, from Roman times this stone was normally shallow quarried from open pits that have been back filled and returned to grazing land. Famous as a decorative facing and ornamental limestone since medieval times because like a ’true’ marble it takes a fine polish; it weathers badly, so has rarely been actually used as a building stone. It is not at all porous but composed of 3D casts of occasionally unbroken broken Viviparus snail shells set in a matrix of weakly cemented broken freshwater bivalve and gastropod shell. Rare examples of its use in Dorset buildings are the ‘marble manors’ along the line of the outcrop stretching from Peveril Point to Worbarrow Bay, in the valley out of Swanage and in which buildings, the weathering is clear to see. Purbeck Marble tomb-top slabs of the 13th century have lasted well into the 19th & 20th centuries inside churches but following Victorian rebuilds or otherwise they have been placed outside, as at Bindon Abbey, Corfe Castle and Kimmeridge churchyards. Sculpted designs and recognisable period styles have been almost or completely weathered away. Drawings and or written records are, in these cases, all of any value that remains. In addition to the easily recognisable articulate/unbroken Viviparus there are also a small number of minor or occasional low salinity biogenic components common to much of the Purbeck stratigraphy and better seen in thin section.

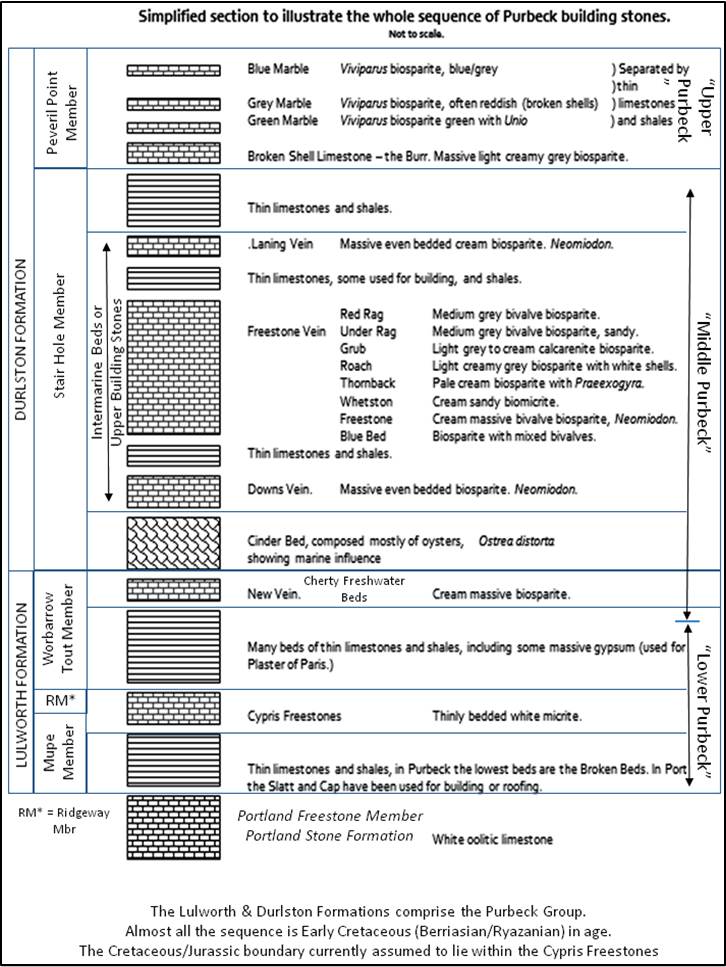

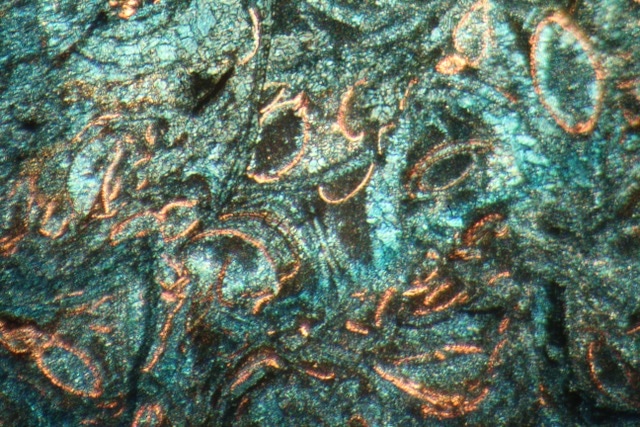

The Purbeck Marble beds, above the Unio Member, Clements 239, might contain the Unio bivalve, which in its youth attaches itself to feed on fish. Two articulate examples are seen close together in this polished altar slab and can be described as ‘nesting’. It appears that both died and their empty shell was filled with the broken shell slightly muddy matrix surrounding them. The muddy brown and darker mixed matrix patches shows this rock to have been well bioturbated by other organisms. This portion of altar stone is yellowish, so would be from the green bed, Unio would be very unexpected in the blue bed.

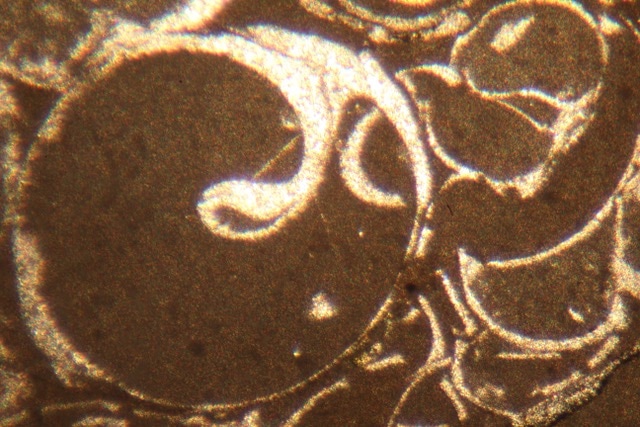

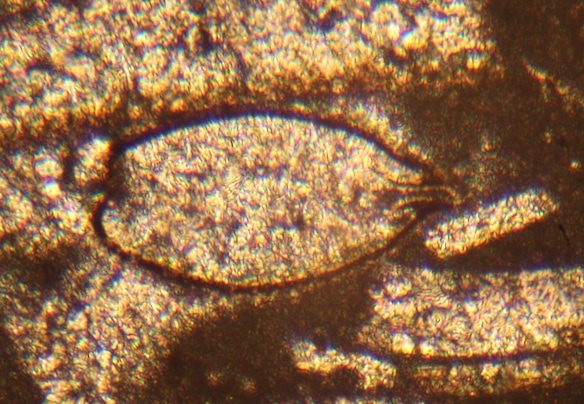

In this section the matrix is all of fine micritic mud which has fully filled this mid-length transverse Viviparus thin section and surrounding shell detritus. The absence of opaque black areas between the bioclasts tells us that in the absence of such vugs/cavities this rock is not porous. The retention of original microfossil shapes tells us that this rock has not been compressed during diagenesis. It is a biomicrudite because the Viviparus in it are more than 1mm in diameter.

|

The best introduction to this stone is probably seen at Salisbury Cathedral where 16,000 tons were used between 1220 & 1258 - notably in the main structural pillars of the nave, decorative facings, shafts and also for facings and pillars of the cloisters outside, where weathering is still well seen despite much replacement up to the present day. Attempts have been made to protect Purbeck Marble used inside from decay using lacquers and polish, especially in early Victorian times before leaking roofs and walls of decaying churches were restored and updated in great numbers. Medieval village churches invariably have good examples of this stone used as facings, tombstones, altars, pillars, fonts, and effigies. Re-cycled pieces are commonly seen as window sills and even in external re-build/repairs of monastic properties where they are immediately evident from their quite unique texture if badly weathered. Also admired for decorative use, very occasionally used together outside Dorset and easy to confuse with Purbeck Viviparus Marble, is the Sussex Paludina Marble of the Early Cretaceous, Wealden. The Victorian names Large and Small Paludina have long survived in the ornamental stone trade to distinguish these two fossil shell limestones, both post Jurassic, so younger and evolved Viviparus fresh-water snail species.

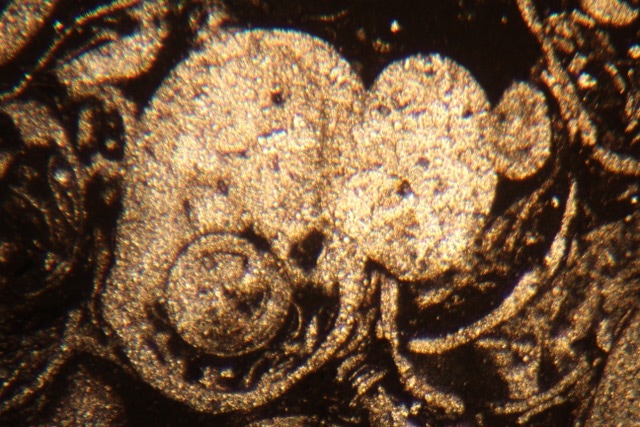

Although there has been compression during the Purbeck diagenesis these photomicrographs of Purbeck marble reveal the original bioclastic content well and much of it unbroken. In the stained section, the original calcitic or chitinous carapace of ostracods has been unchanged. The dyes have stained the ostracod shells pink and the later ferroan calcite blue. The loose carapace valves are shed as the crustacean grows.

Ostracods are a common crustacean feature of semi-freshwater environments and the Cypridea setina setina, length 0.96mm, is common in the Upper Purbeck beds - and in unstained section, the carapace is revealed in a sharp but darker outline.

Where empty snail shells don’t fully fill with surrounding sediment and retain unfilled cavities, the remaining spaces commonly fill with calcium rich fluids during diagenesis and new sparite crystals will grow together to fill this space. This calcite is known as secondary calcite and is not original to the bioclastic structures. (Gravity ensures that mud fill, matching the rest of the matrix will settle matchingly in the lower parts of adjacent gastropod shells and the bright transparent secondary sparite fills all or most of space above the in-shell mud.) This is known as Geopetal structure in thin sections and tells the observer the 'right way up' to interpret vertically sawn thin sections. Many single shell molluscs have their newest/youngest sections filled with sparite including Viviparus and ammonites.

|

Colouring of Purbeck Limestone Group, by Durlston Bay bed numbers of R.G.Clements. 1992. from Consultations with J. Haysom, Brian Bugler. 2018.

Where colour is given in any name by Clements he attributes that name to Cosgrove & Hearne 1966. However, those colours were misleading because their Red Marble is really green when quarried unless oxygenated water had already oxidised the iron in situ. So the Red Marble bed DB 241 is normally quarried and remains a greenish colour, unless commonly somewhat oxidised and is now considered the green bed. Therefore, the once Green Marble bed D237 is now considered the Grey bed. Hence, here in descending stratigraphic order by Clements Bed Numbers, here are bed names by colour and tendencies for colour oxidisation of iron in Purbeck Marbles - to yellow, rust or red:

244c Viviparus limestone - 'Purbeck Marble blue bed.’ - oxidation rare - see C.11th Temple church London & C.19th St. James church, Kingston, Purbeck. Wells Cathedral has exceptions; Reddened blue recessed shafts in compound piers & a floor tomb ledger. Maximum thickness 0.11 m.

241 Viviparus limestone - ‘Purbeck Marble green bed’ - not uncommonly this bed oxidises to red in situ or in subsequent use - see x2 ledger slabs at Wimborne Minster and also to yellow/orange in altar at Folke, Sherborne. Maximum thickness 0.81 m.

237 Viviparus biosparite. - 'Purbeck Marble grey bed’ - overall stone colour remains grey with brighter whites of calcite in shell, or calcite filled intra-shell pores. The colour tones of calcite in both shell and grain pores will vary. Maximum thickness 0.38m.

The lowest Purbeck Marble, the pre-Unio grey bed, Clements 237 is only 150 - 200 mm. thick. It may also be laminated and has been ideally used for pillars and colonettes. Maximum thickness 0.20m.

Where colour is given in any name by Clements he attributes that name to Cosgrove & Hearne 1966. However, those colours were misleading because their Red Marble is really green when quarried unless oxygenated water had already oxidised the iron in situ. So the Red Marble bed DB 241 is normally quarried and remains a greenish colour, unless commonly somewhat oxidised and is now considered the green bed. Therefore, the once Green Marble bed D237 is now considered the Grey bed. Hence, here in descending stratigraphic order by Clements Bed Numbers, here are bed names by colour and tendencies for colour oxidisation of iron in Purbeck Marbles - to yellow, rust or red:

244c Viviparus limestone - 'Purbeck Marble blue bed.’ - oxidation rare - see C.11th Temple church London & C.19th St. James church, Kingston, Purbeck. Wells Cathedral has exceptions; Reddened blue recessed shafts in compound piers & a floor tomb ledger. Maximum thickness 0.11 m.

241 Viviparus limestone - ‘Purbeck Marble green bed’ - not uncommonly this bed oxidises to red in situ or in subsequent use - see x2 ledger slabs at Wimborne Minster and also to yellow/orange in altar at Folke, Sherborne. Maximum thickness 0.81 m.

237 Viviparus biosparite. - 'Purbeck Marble grey bed’ - overall stone colour remains grey with brighter whites of calcite in shell, or calcite filled intra-shell pores. The colour tones of calcite in both shell and grain pores will vary. Maximum thickness 0.38m.

The lowest Purbeck Marble, the pre-Unio grey bed, Clements 237 is only 150 - 200 mm. thick. It may also be laminated and has been ideally used for pillars and colonettes. Maximum thickness 0.20m.

Other references:

1. "An engineering perspective on the Archaeology of the Purbeck Stone Industrial Industry''. 1978 Geoffrey Norris Ph.D. thesis Bournemouth University.

Link to document

2. 'An investigation into the use of Purbeck Marble in medieval England'. Harrison & Son, Hartlepool 1978 R. Leach (out of print)

3. The Use of Purbeck Marble in Medieval Times’. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society Vol. 70 p. 74-98, G. Drury. 1948

1. "An engineering perspective on the Archaeology of the Purbeck Stone Industrial Industry''. 1978 Geoffrey Norris Ph.D. thesis Bournemouth University.

Link to document

2. 'An investigation into the use of Purbeck Marble in medieval England'. Harrison & Son, Hartlepool 1978 R. Leach (out of print)

3. The Use of Purbeck Marble in Medieval Times’. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society Vol. 70 p. 74-98, G. Drury. 1948

Text and photos by PJB with additional photos by JT and WGT.