Church of St. George, Fordington, Dorchester. Grade: 1, NGR: SY69853 90561

Lead author: PS

|

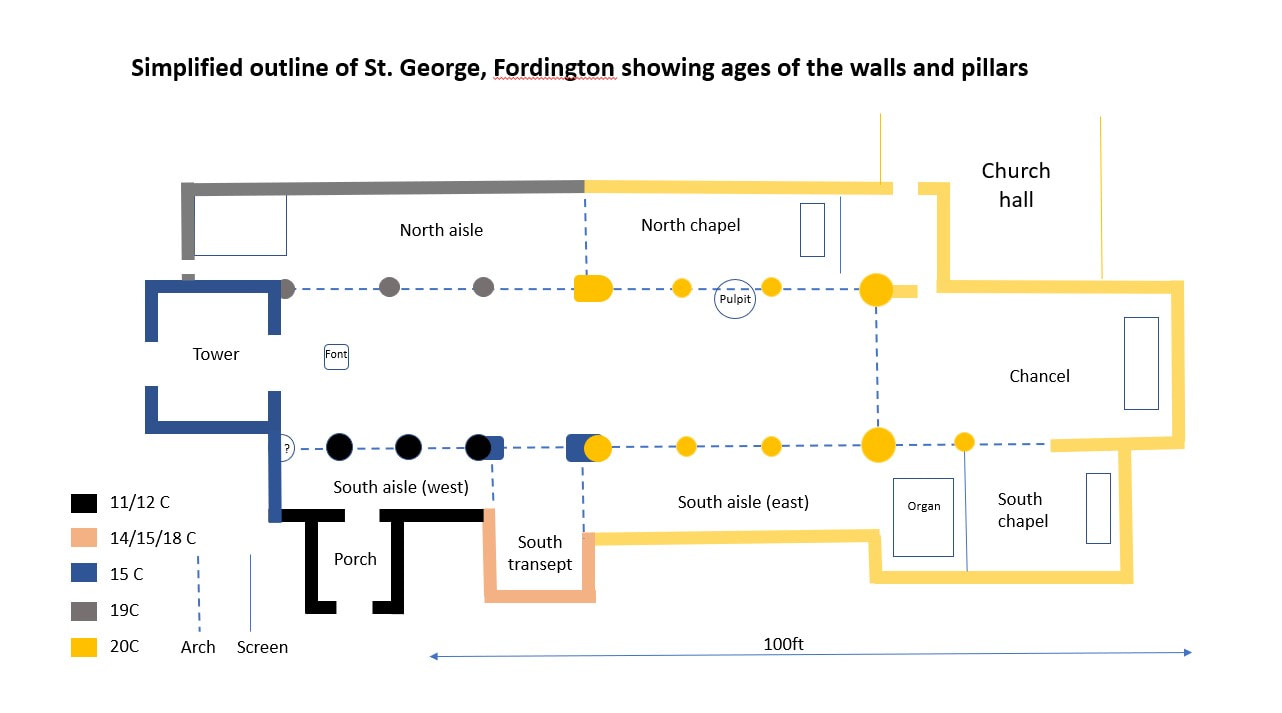

Until the 20th century Fordington was a village in its own right. It now forms the eastern side of Dorchester. The church (1) has a history extending back at least to the 12th century. The west end of the church is built over a Roman cemetery. In excavations made in 1907, old foundations were revealed indicating that a church stood on the site before the earliest parts of the present church.

Parts of the south arcade, the south aisle and the south porch were built late in the 12th and early 13th century. The south transept was added probably in the 14th century but altered in the mid-18th century. |

A north transept was never built. The west tower was added in the late 15th century and the south porch rebuilt. In 1833 a new chancel, a north aisle and a north arcade were built. In 1907, the new vicar at Fordington, Rev. R. Grosvenor Bartelot, initiated a major rebuilding programme to extend the nave and south aisle, replace the 1833 chancel and build a south chapel. The work was finally completed in 1927.

The exterior

The main exterior building stones are Middle Purbeck limestones, Portland limestone, Purbeck Cypris Freestone and Ham Hill stone from Somerset.

The windows

The windows in all the walls which date from 1907 to 1926 are of the same design and are all Portland limestone with a Ham Hill stone surround (14a). The four windows at the west end of the north aisle (1833) have a Portland limestone surround but no mullions or tracery (5a). The 15th century window in the south wall of the south transept has Ham Hill stone mullions and tracery with a Portland stone surround (12).

The main exterior building stones are Middle Purbeck limestones, Portland limestone, Purbeck Cypris Freestone and Ham Hill stone from Somerset.

The windows

The windows in all the walls which date from 1907 to 1926 are of the same design and are all Portland limestone with a Ham Hill stone surround (14a). The four windows at the west end of the north aisle (1833) have a Portland limestone surround but no mullions or tracery (5a). The 15th century window in the south wall of the south transept has Ham Hill stone mullions and tracery with a Portland stone surround (12).

The roof has slates and tiles. The balustrade, where present, is Ham Hill Stone.

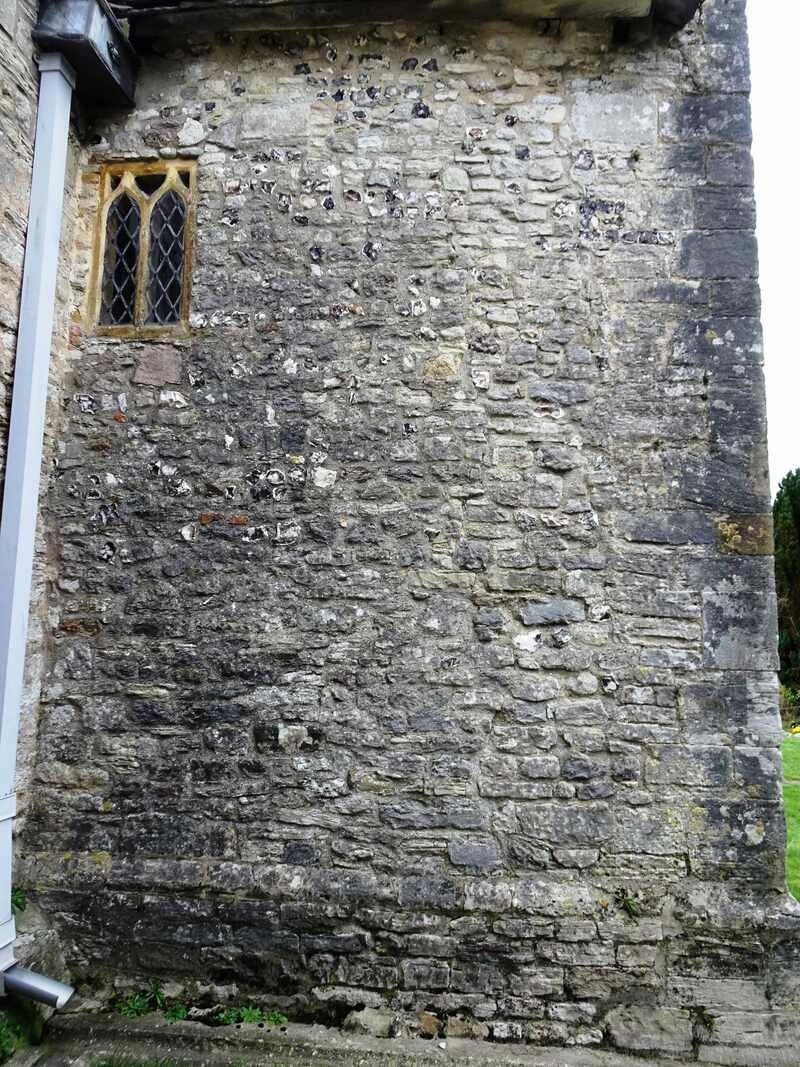

The north aisle walls (2)

The eastern bays of the north wall were built when the church was widened in 1907 onwards. They are ashlar blocks of Middle Purbeck limestone (3a, 3b) in assorted sizes. A church hall of brick (1989) has since been built at right angles to the east end of the north aisle (4).

The north aisle walls (2)

The eastern bays of the north wall were built when the church was widened in 1907 onwards. They are ashlar blocks of Middle Purbeck limestone (3a, 3b) in assorted sizes. A church hall of brick (1989) has since been built at right angles to the east end of the north aisle (4).

The western bays (1833) are built with ashlar Portland limestone (5a, 5b).

The Ham Hill stone balustrade is absent and grey slates are visible on the roof. The buttresses supporting all six bays are Portland limestone (6a, 6b).

The west wall of the north aisle (7a, 7b) is built with small blocks of rubble Purbeck Cypris Freestone with occasional blocks of Ham Hill stone, Portland limestone and Flint.

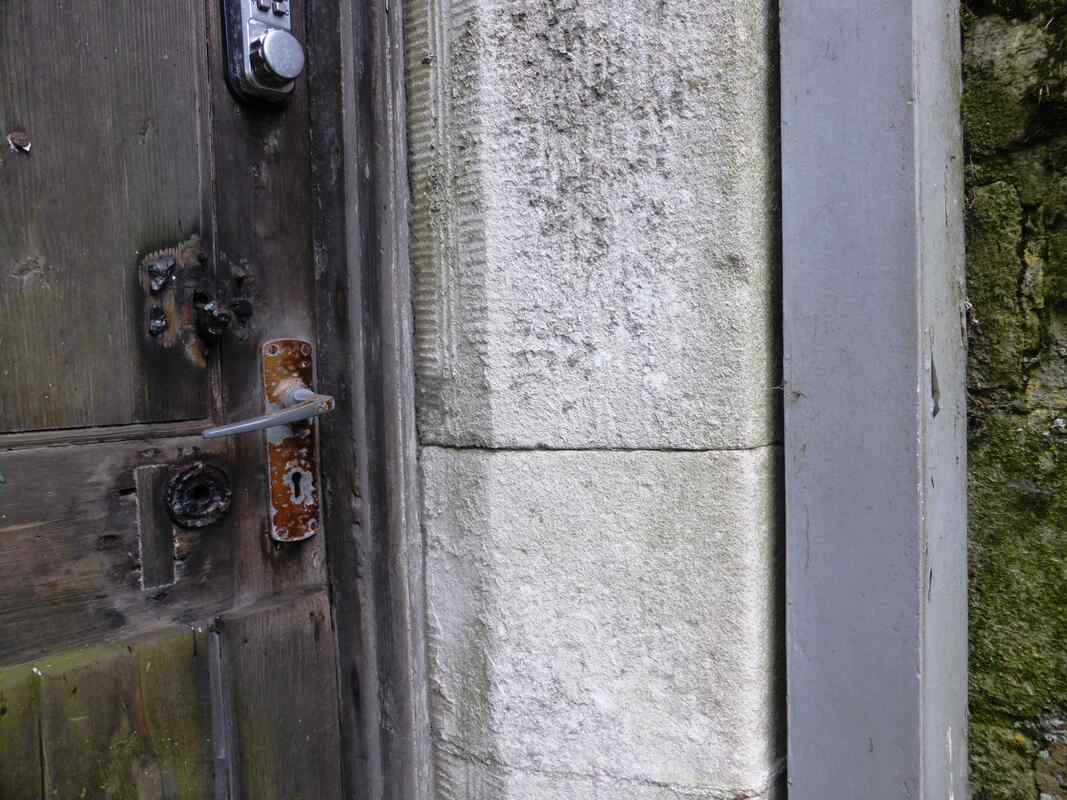

The north aisle doorway is Portland limestone (8a, 8b, 8c).

The south and east walls of the aisles and the south transept

The walls of the south aisle and the south transept at the western end are all mainly rubble Purbeck Cypris Freestone but they are of different dates (see church plan) (9, 10).

The walls of the south aisle and the south transept at the western end are all mainly rubble Purbeck Cypris Freestone but they are of different dates (see church plan) (9, 10).

The south transept (15th century partly rebuilt in the 18th century) is also built of rubble blocks of Cypris Freestone (11, 12) but has some flints and occasional blocks of Ham Hill stone. There is some brickwork at the apex of the south wall (12).

The south aisle walls east of the south transept were built in stages between 1907 and 1927. They have a brick base which is visible at ground level in some places (13a, 13b).

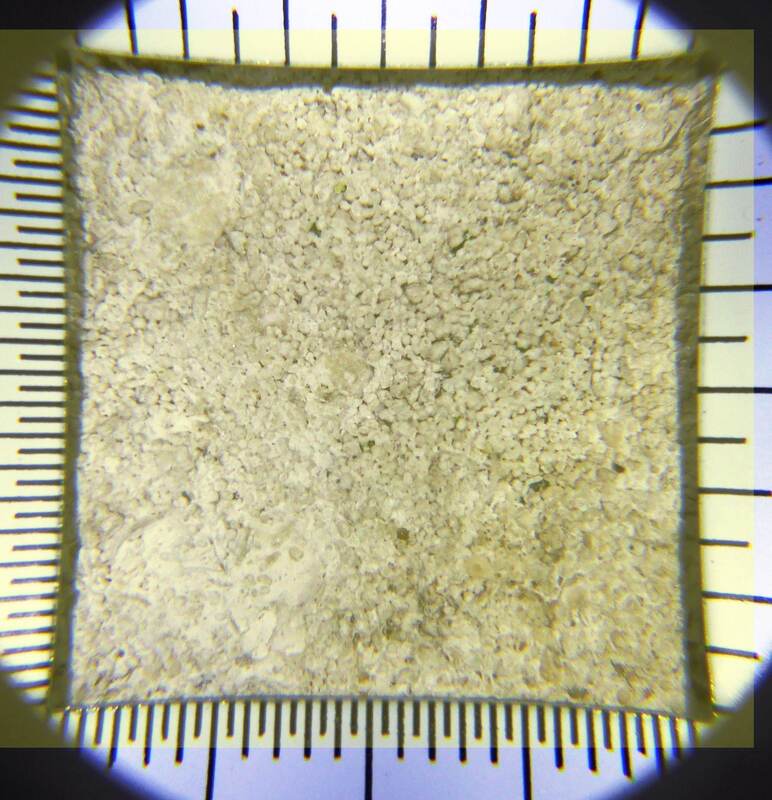

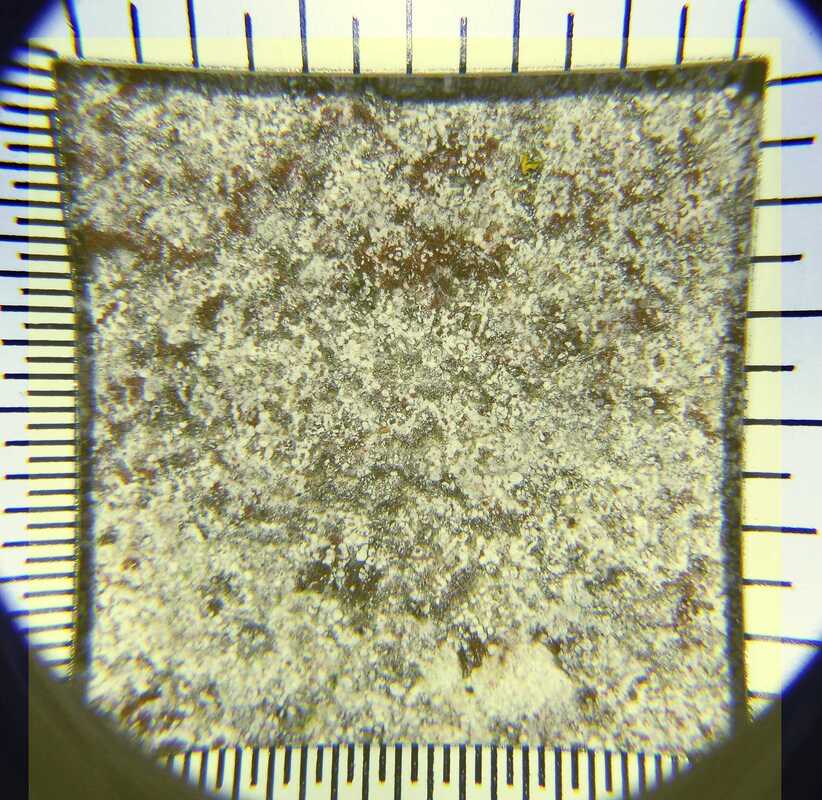

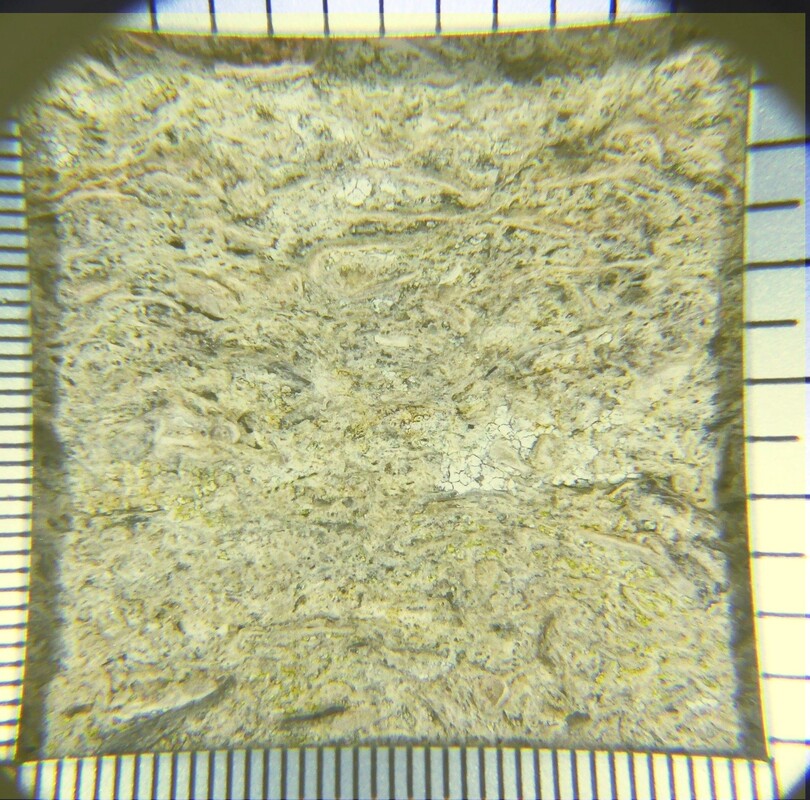

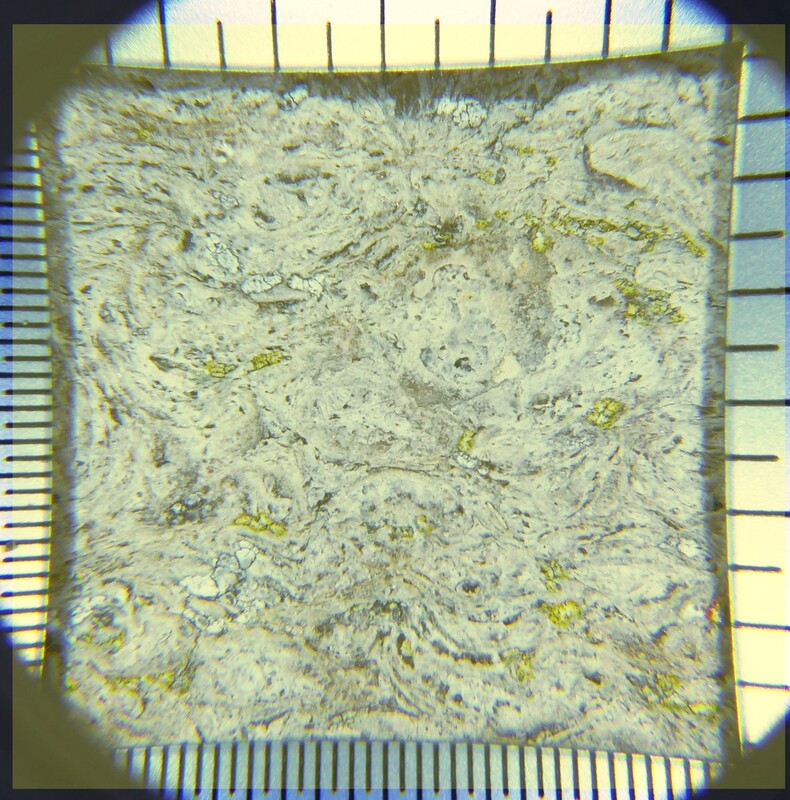

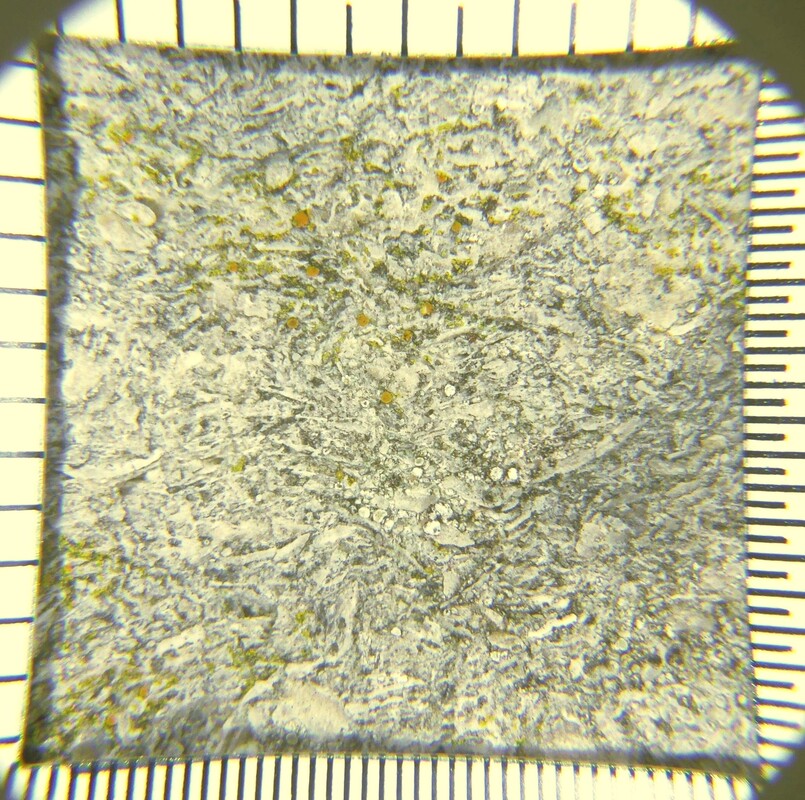

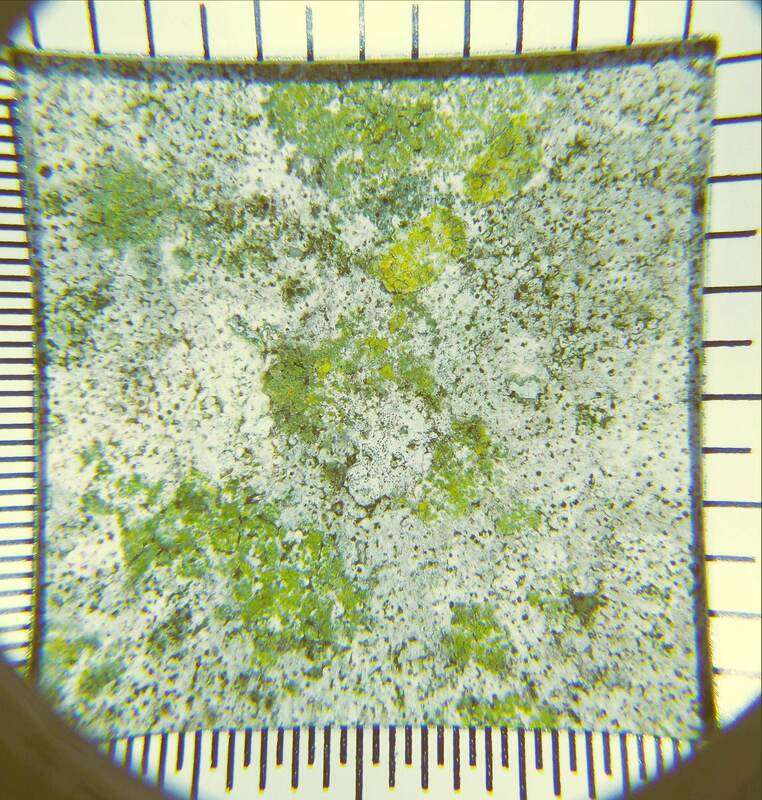

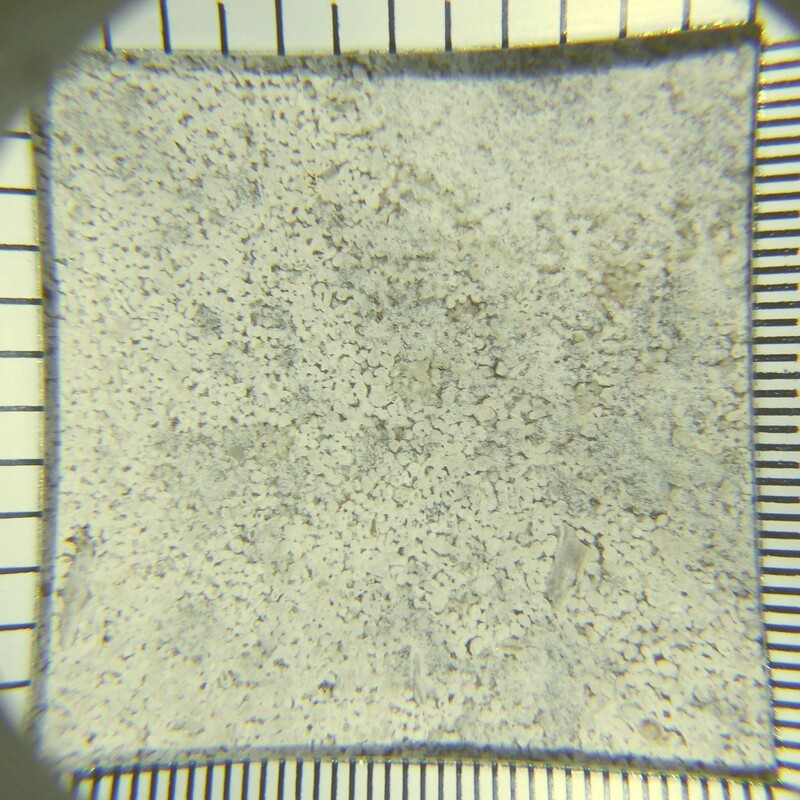

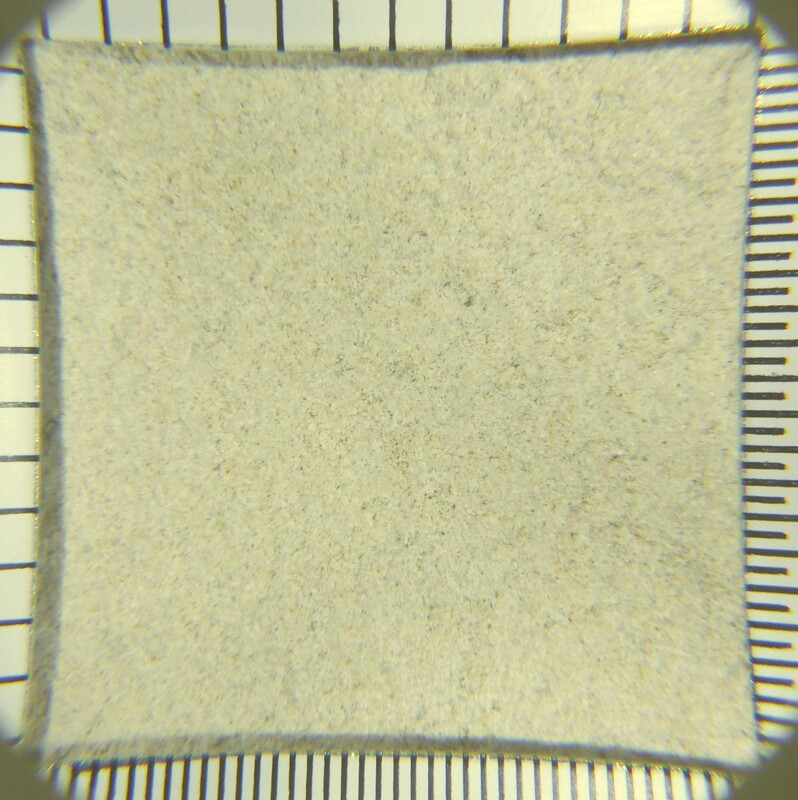

The stone in the walls below the Ham Hill stone string course belong to the Middle Purbeck (14a) and layers of broken shell are visible under magnification. Many of the stones have horizontal splits (often called vugs) (14b).

The stone has probably been extracted from more than one Purbeck bed as the blocks vary in structure (15a, 15b, 15c, 15d).

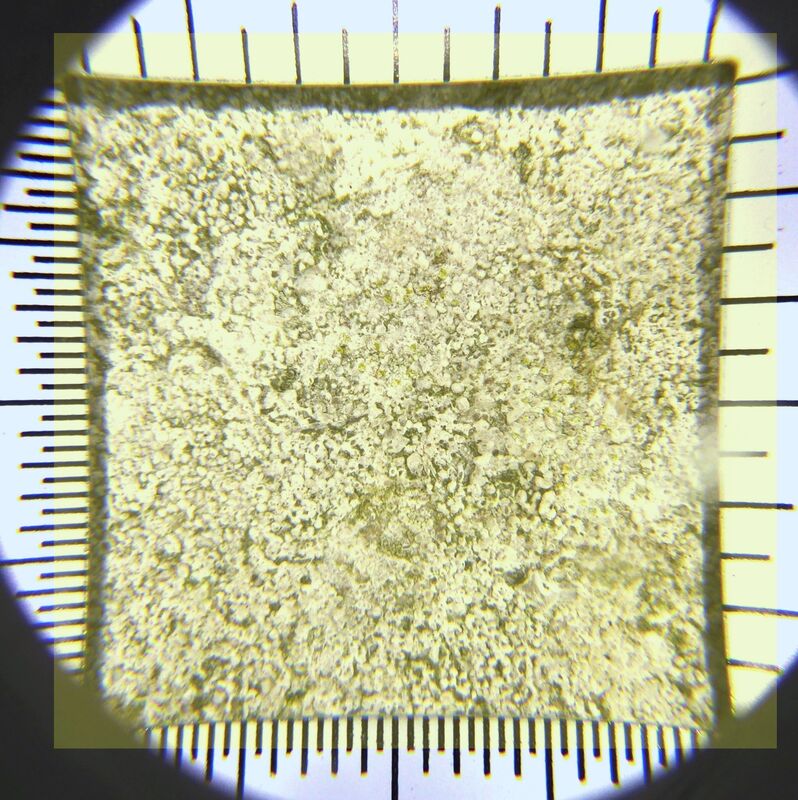

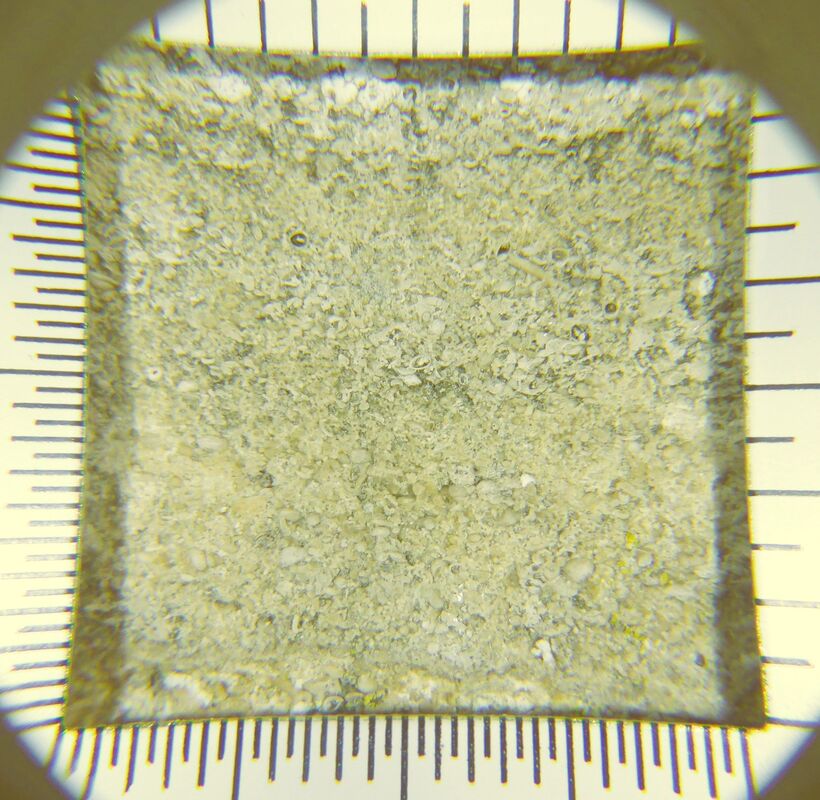

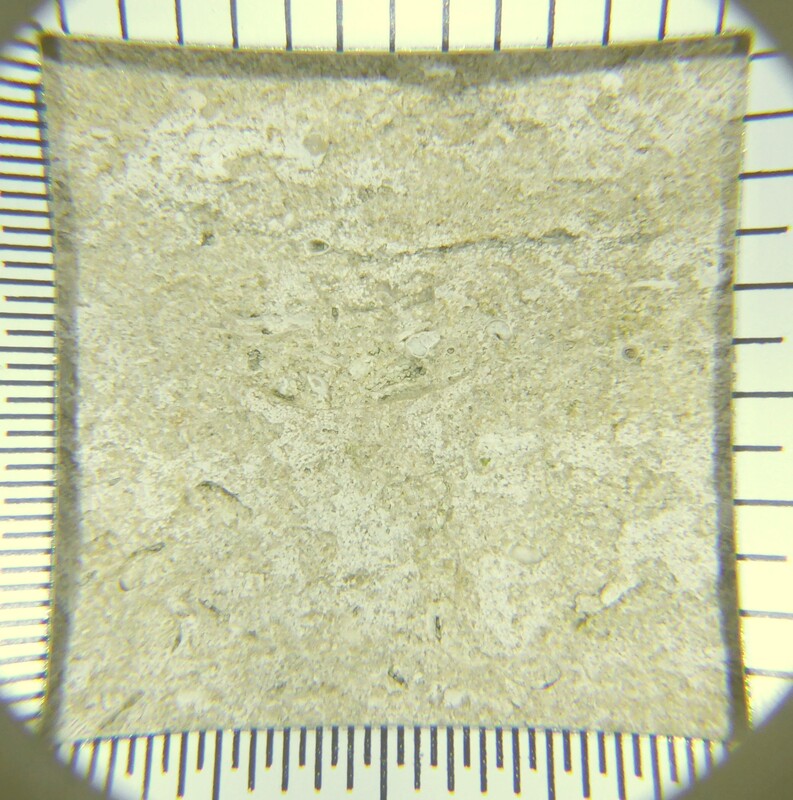

The larger blocks of ashlar stone above the string course are denser and the broken shell is more closely packed with few splits (16a, 16b). Is this Purbeck Burr?

The east wall (17) of the south chapel was in the last phase of the rebuilding programme. The stone matches the Purbeck stone in the south walls but an inset carved date stone in the east wall of the south chapel, dated 1927 is Portland limestone (18a, 18b).

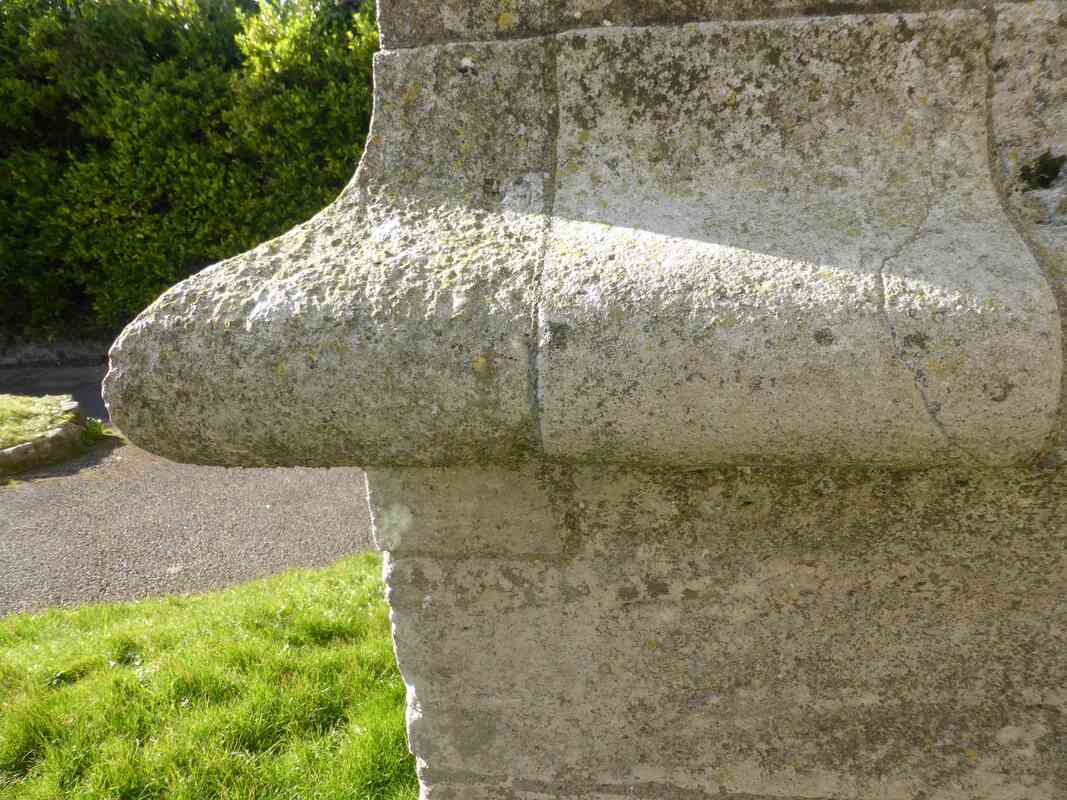

The west tower (built 1485) (19)

The walls, plinth and buttresses are built of ashlar blocks of Purbeck Cypris Freestone (20a, 20b, 20c, 21a, 21b).

The walls, plinth and buttresses are built of ashlar blocks of Purbeck Cypris Freestone (20a, 20b, 20c, 21a, 21b).

Click here to The string courses, balustrade and windows are Ham Hill Stone. The west front (22) and west doorway are also made of blocks of Cypris Freestone (23-26).

The south porch

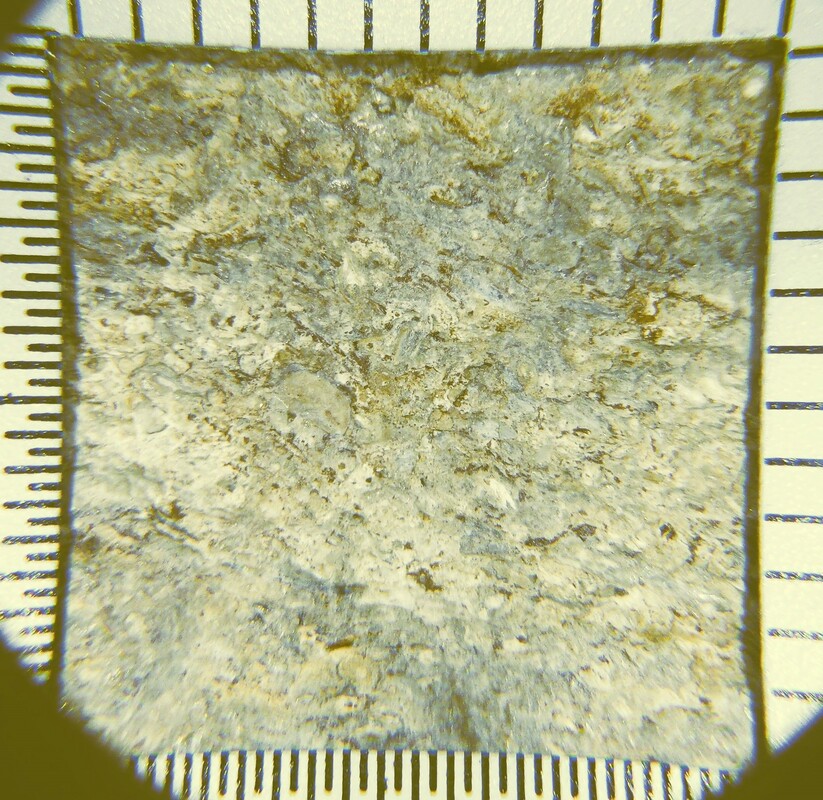

This was partly rebuilt in the 15th century. The walls are mainly Purbeck Cypris Freestone rubble. The 12th century west wall (27a and 27b) also contains a number of flints as well as a small number of rubble blocks of Upper Purbeck Burr (Broken Shell Limestone) (28a, 28b) and some sandstone (29a, 29b).

This was partly rebuilt in the 15th century. The walls are mainly Purbeck Cypris Freestone rubble. The 12th century west wall (27a and 27b) also contains a number of flints as well as a small number of rubble blocks of Upper Purbeck Burr (Broken Shell Limestone) (28a, 28b) and some sandstone (29a, 29b).

The east wall (30) has a small trefoil window inset which is Ham Hill Stone but has a preservative coating. It is possibly a survivor from an earlier (11th century) church on the site.

The south wall (31a) was rebuilt in the 15th century and also contains 13th century stonework. It also consists of small coursed bricks of Cypris Freestone with some larger blocks towards the base, probably from the early church. The sides of the outer doorway are Portland Limestone with some Ham Hill Stone (31b) . The inner doorway (32a) is thought to be a survivor from an earlier church (11th century). It is Ham Hill stone. A carved tympanum of Caen stone (cited in literature but not confirmed) sits above the doorway (32b). Vestiges of paint suggest that it was once coloured.

Note: The carving is said to represent St. George on horseback with praying soldiers on the left, and dead or dying soldiers on the right and to represents St. George's miraculous intervention in the Battle of Antioch. The Battle of Antioch (1098) was a military engagement fought between the Christian forces of the First Crusade and a Muslim coalition led by Kerbogha, atabeg of Mosul. The legend is that St. George is said to have fought a dragon outside the walls of Antioch.

References

1) J. Feacey, DNH&AS Vol 30, (1909), p. 164–95

2) Hill M., Newman J., Pevsner N. (2018), The Buildings of England, Dorset, Yale U. Press, p.246-7

3) https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101292171-church-of-st-george-dorchester

1) J. Feacey, DNH&AS Vol 30, (1909), p. 164–95

2) Hill M., Newman J., Pevsner N. (2018), The Buildings of England, Dorset, Yale U. Press, p.246-7

3) https://britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101292171-church-of-st-george-dorchester

The Interior (33)

The interior from the south transept eastwards was rebuilt in the 20th century. At the west end the interior walls of the aisles are plastered. The walls at the east end are faced with ashlar stone (see the east end). When the Nave floor was replaced in 1907, pre-Christian graves were found cut into the Chalk on which the church is built.

The interior from the south transept eastwards was rebuilt in the 20th century. At the west end the interior walls of the aisles are plastered. The walls at the east end are faced with ashlar stone (see the east end). When the Nave floor was replaced in 1907, pre-Christian graves were found cut into the Chalk on which the church is built.

The area immediately to the east of the tower has no seating but has several items of interest. The 15th century font (34a, 34b) is Ham Hill stone on a pedestal and base of the same stone.

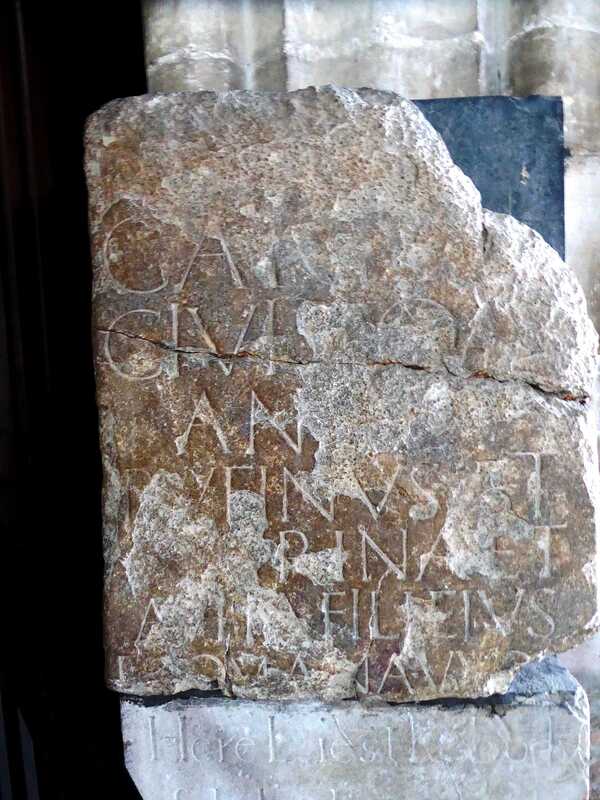

A Roman grave marker (35a) is against the tower arch pillar. It is Purbeck Marble (35b). The inscription reads “For Carinius a Roman citizen aged 50 years. His children Rufinius, Carina and Avita with his wife Romana set up this memorial”. The stone was discovered during reconstruction of the porch in 1907.

The nave arcades

The pillars of the nave range in date from the 12th to the 20th century (see plan) (36, 37, 38).

The pillars of the nave range in date from the 12th to the 20th century (see plan) (36, 37, 38).

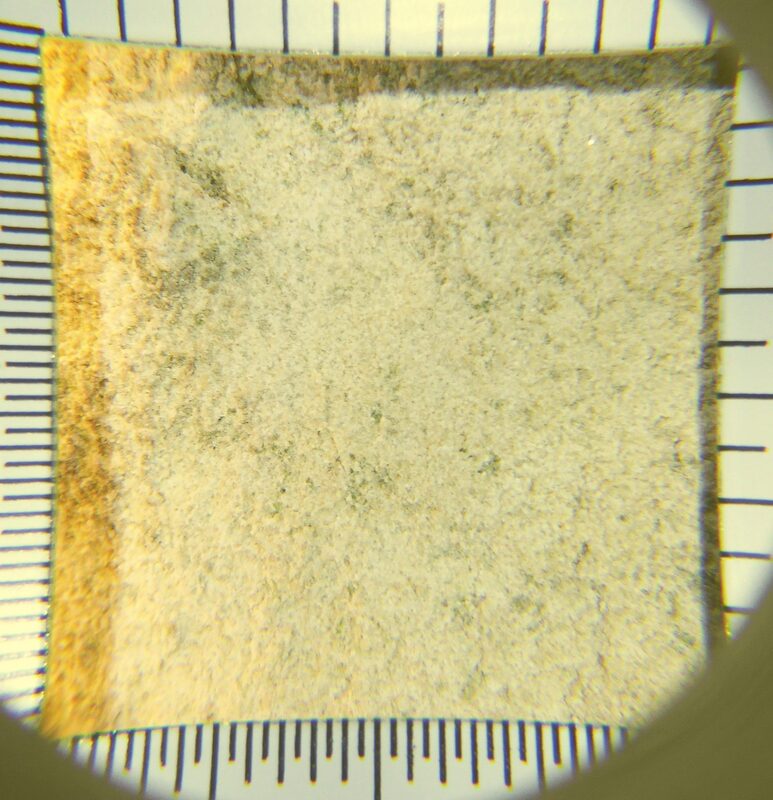

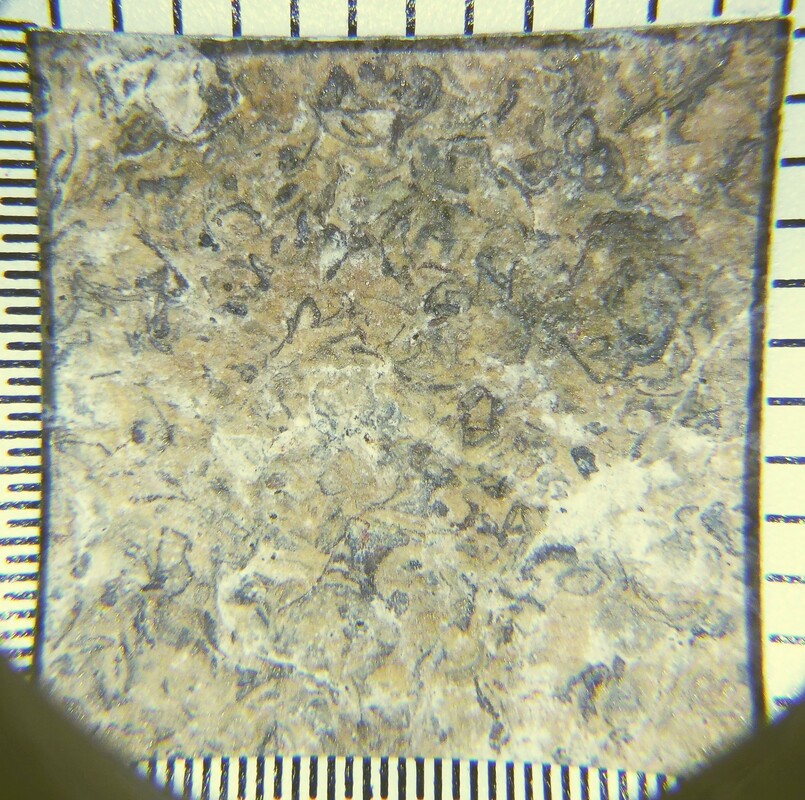

The older arcading (12th century, 15th century and 1833) of both north and south aisles is probably all Ham Hill Stone. It is important not to be misled by the colour of the pillars as their pale appearance is due to a generous coating of plaster or lime wash. Feary in his article (Ref. 1 p16) describes the 12th century columns as being Beer Stone and Ham Hill Stone. There does not appear to be any Beer Stone present. Close inspection with the aid of loupe photography of thinner parts of the coating revealed an ochre/brown-coloured stone beneath (39b, 39c) probably Ham Hill Stone.

The archway into the north chapel (40a) was built in 1833 to match the 15th century archway to the east of the south transept (40b). Both are Ham Hill Stone. The 20th century columns are Middle Jurassic Doulting limestone on Ham Hill Stone bases (see ‘The east end of the church’ below).

|

The south transept has a mixed history. It was originally built in the 14th century, altered in the 15th and again in the 18th. The archway is Ham Hill stone. It also contains two very early Ham Hill stone roundels with incised crosses (41) now embedded in the south wall and flanking the south window, early mediaeval, perhaps 11th-century, reset (presumably from the 1907 excavations).

The pulpit (1592) (42a) This is one of the first stone pulpits to be made after the Reformation. It has been placed in several different positions in the church, each change being recorded in a carved shield cartouche on the pulpit, the first being in the reign of Elizabeth I (42b). The dates 1833 and 1912 also appear. Again, the true colour of the stone is obscured by whitewash. It is probably Ham Hill Stone. |

The altar in the south chapel – The Edward Chapel

The stone altar (43a) in the south chapel dated to 1390 was brought from Salisbury Cathedral in 1958–9, where previously it had been adapted by James Wyatt as the high altar. Subsequently, it was moved to the Lady Chapel and eventually relegated to the cloister. The present front in five bays is probably the original length; the ends have been reduced to the present 1½ bays. The stone is Portland limestone (Chilmark) from the Vale of Wardour (43b).

The stone altar (43a) in the south chapel dated to 1390 was brought from Salisbury Cathedral in 1958–9, where previously it had been adapted by James Wyatt as the high altar. Subsequently, it was moved to the Lady Chapel and eventually relegated to the cloister. The present front in five bays is probably the original length; the ends have been reduced to the present 1½ bays. The stone is Portland limestone (Chilmark) from the Vale of Wardour (43b).

The link between Salisbury and Fordington is buried deep in history. Before 1066 Fordington was a royal manor but William the Conqueror gave parts of Fordington to St. Osmund who became to first Bishop of Salisbury. He endowed Salisbury Cathedral with the church and its lands and St. George became a Prebendal church (Fordington Church History pamphlet).

The east end of the church (1907 – 1928)

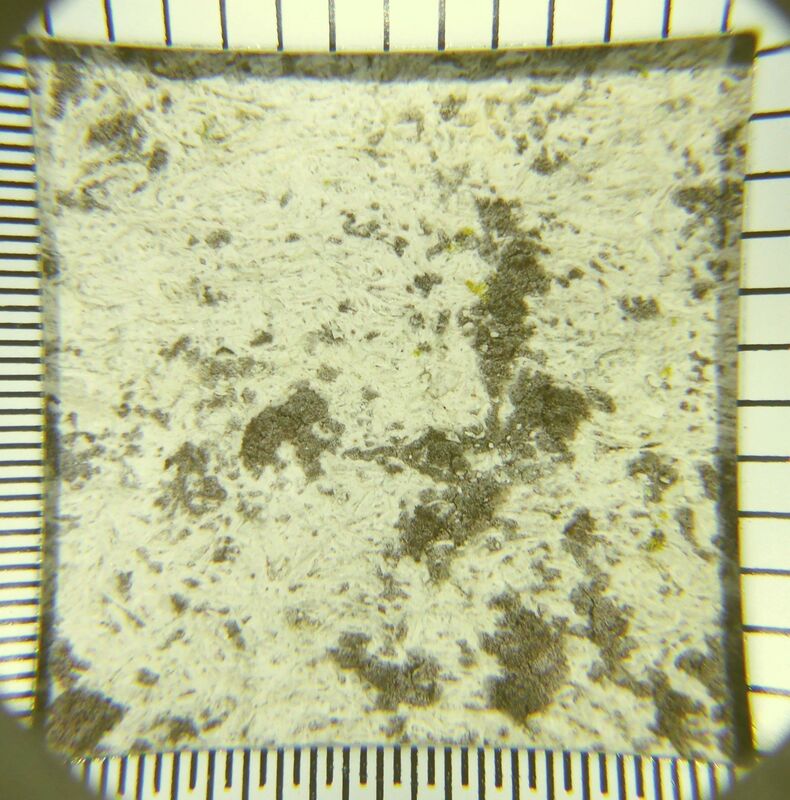

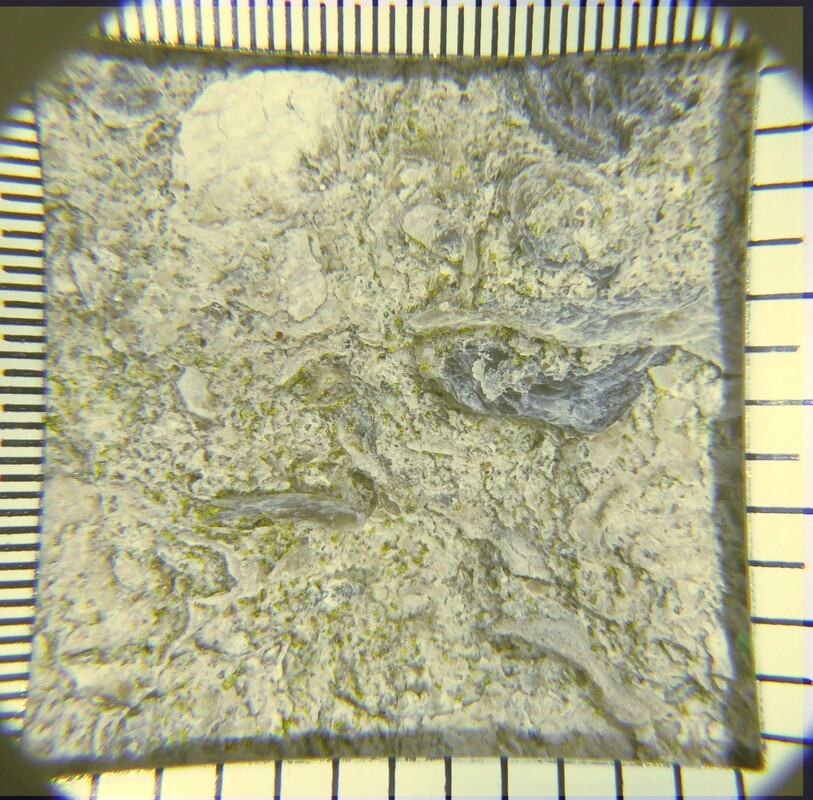

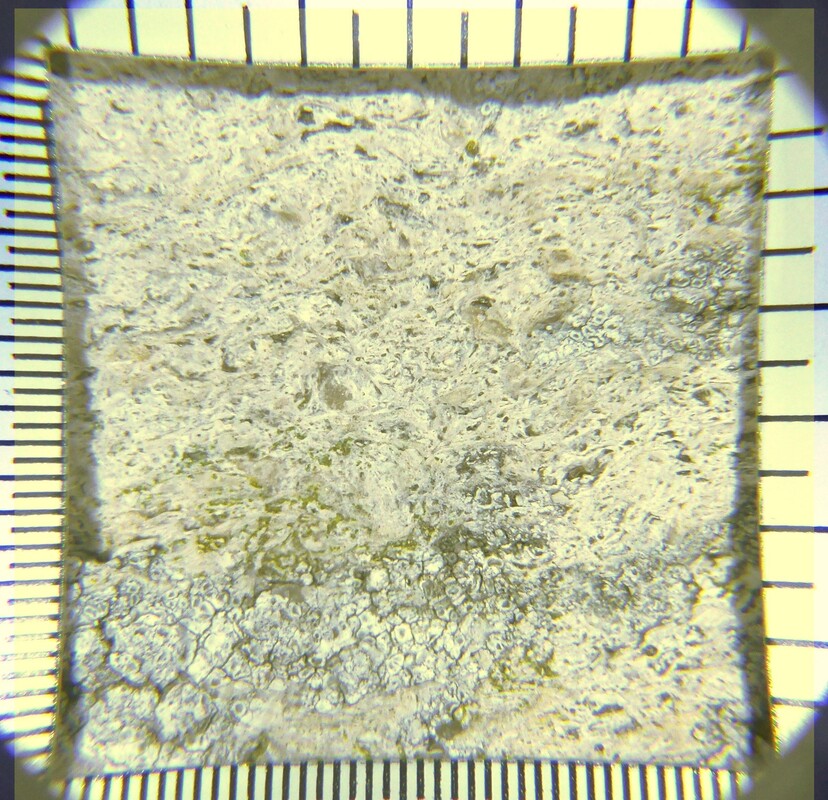

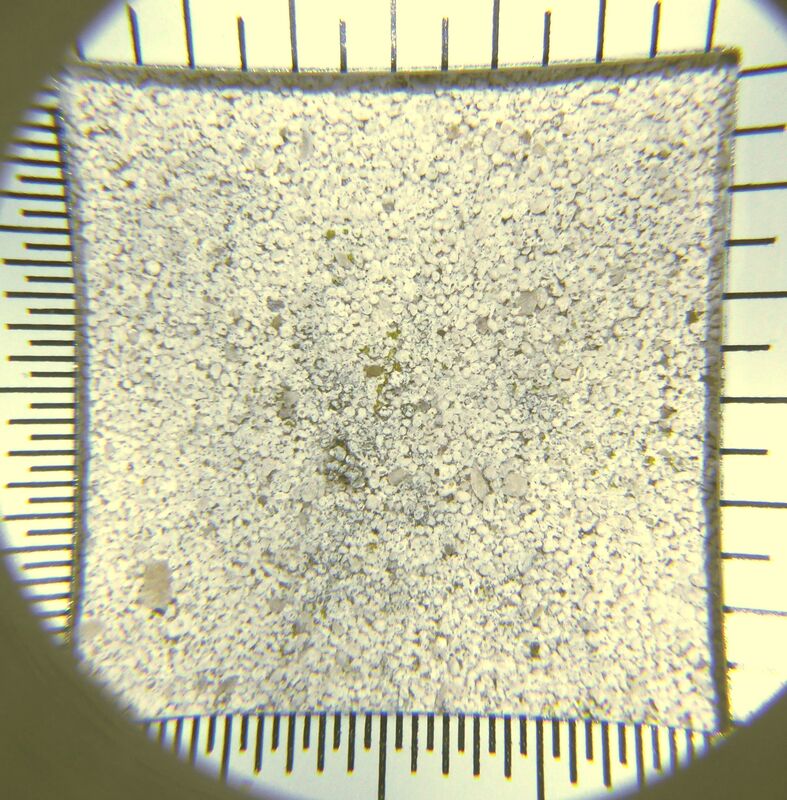

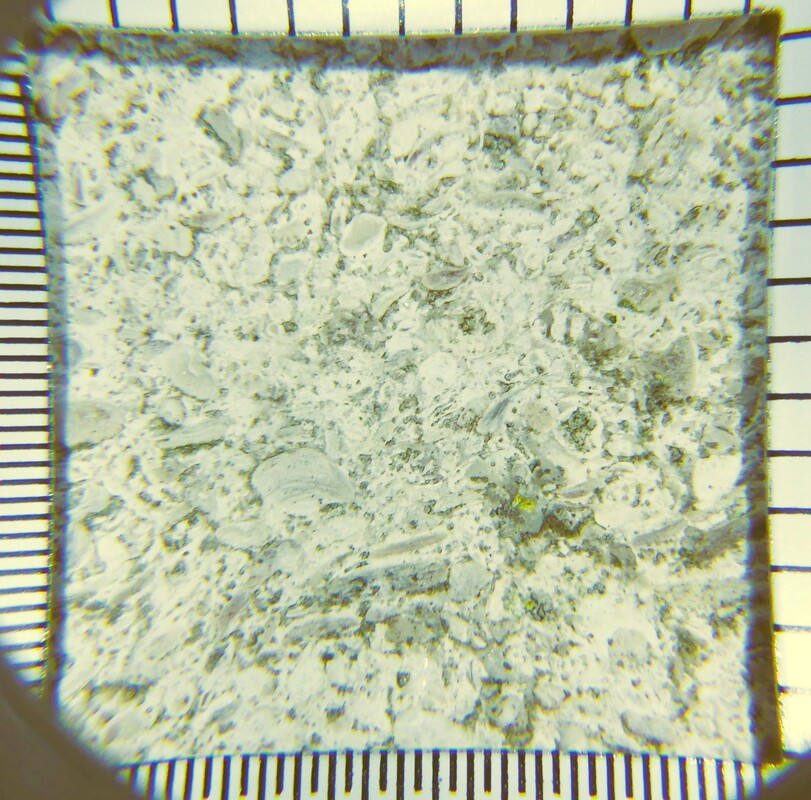

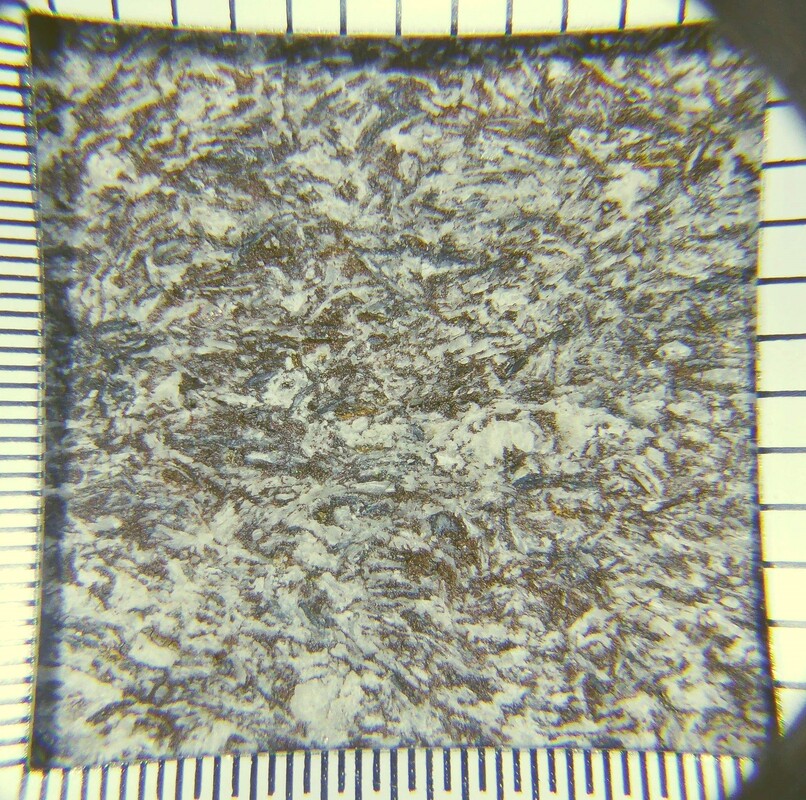

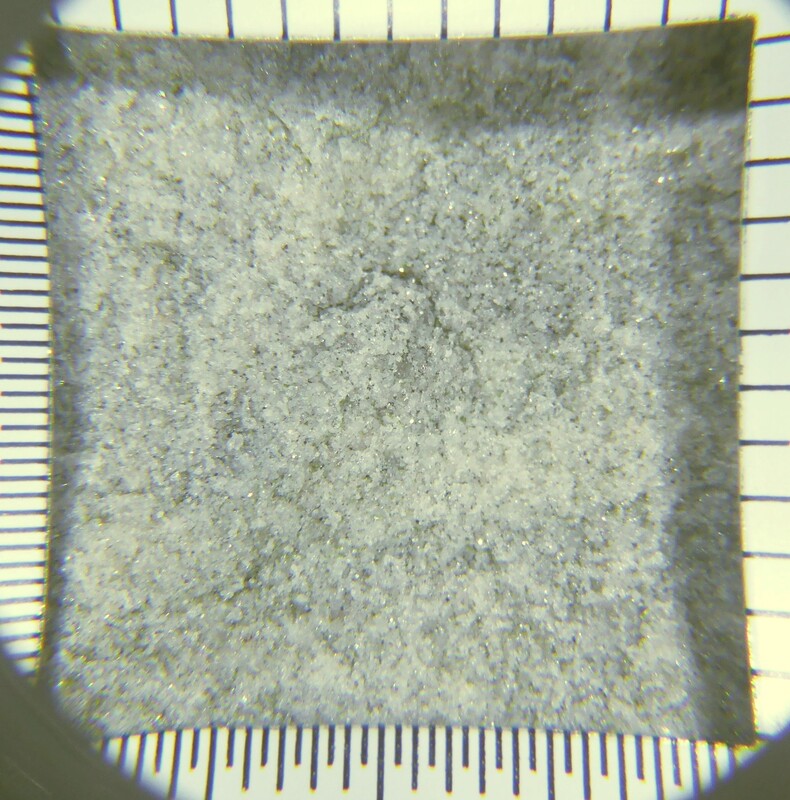

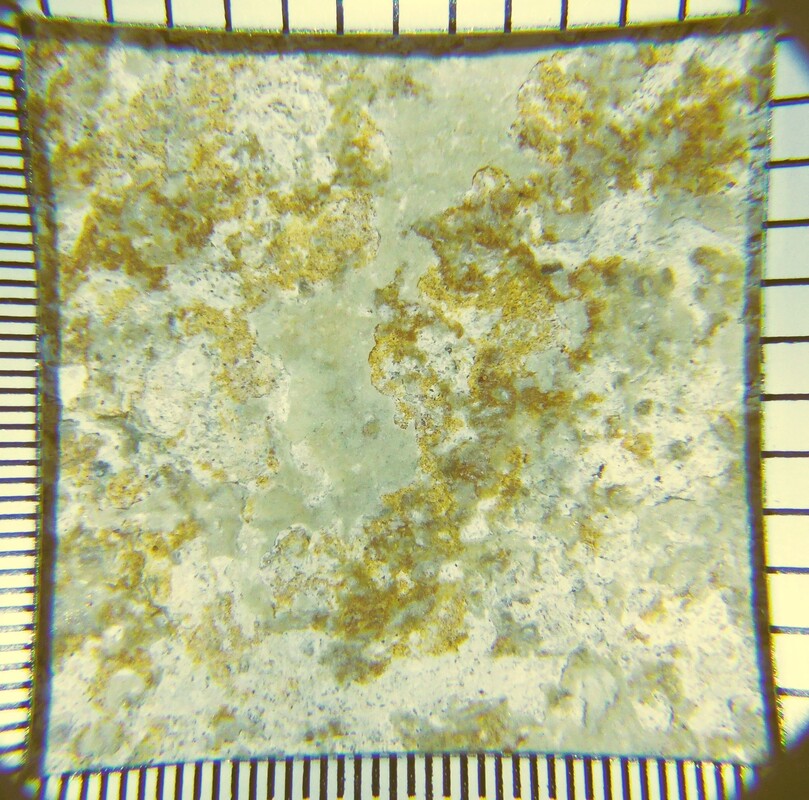

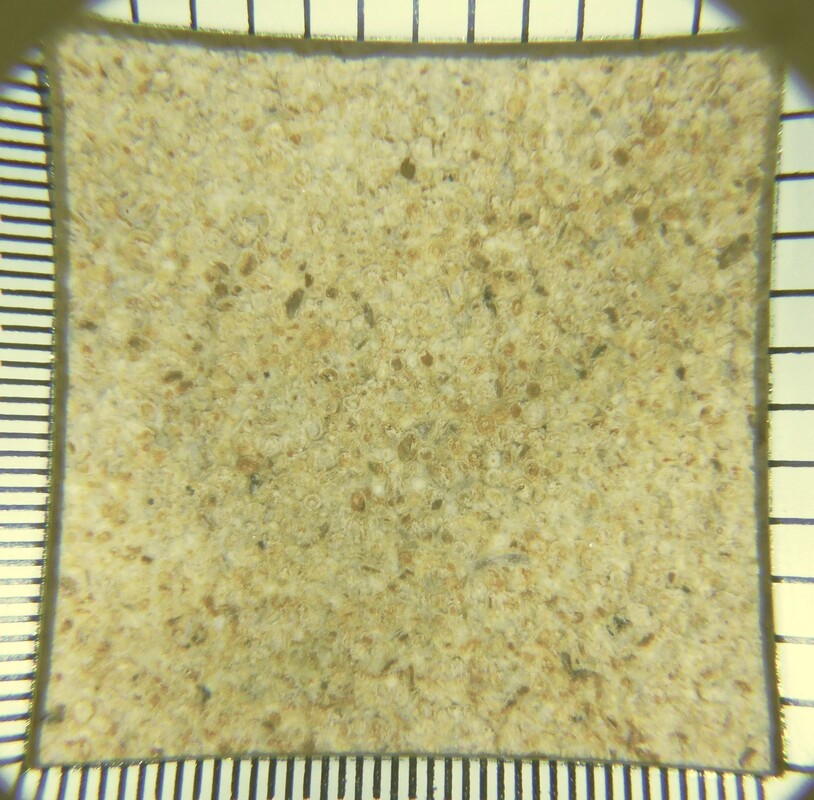

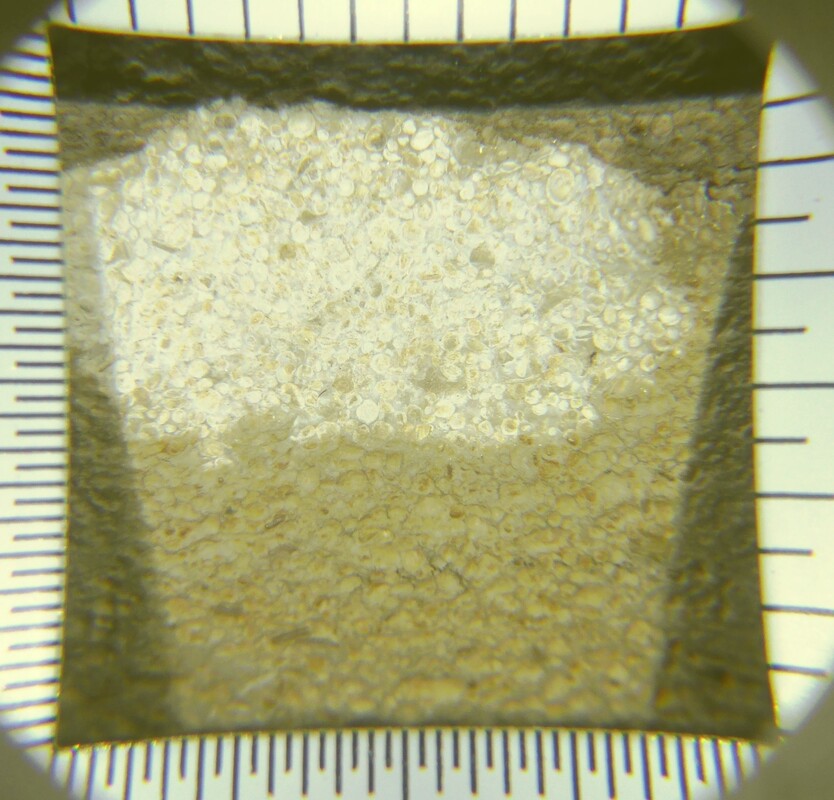

Whilst rebuilding was started in 1907, the eastern end was completed in stages with long intervals between including a fire in the roof in 1912. The final phase, the south chapel adjacent to the chancel, was completed in 1927. Its twin on the north side was never built. A contract was signed in 1907 with Trask & Sons, Stoke-sub-Hamdon for stone to re-build the east end of the nave. The obvious choice, therefore is that it should be Ham Hill stone as, at first glance the ashlar stonework has the same orange-brown colouring. However, Ham Hill Stone is a shell brash limestone whereas the stone supplied and used at the east end is an oolitic limestone. The stone actually used for the rebuilding was Doulting Stone, a Middle Jurassic stone in the Inferior Oolite group identified by its ooidal appearance when viewed under magnification. It often contains crinoid debris.

Whilst rebuilding was started in 1907, the eastern end was completed in stages with long intervals between including a fire in the roof in 1912. The final phase, the south chapel adjacent to the chancel, was completed in 1927. Its twin on the north side was never built. A contract was signed in 1907 with Trask & Sons, Stoke-sub-Hamdon for stone to re-build the east end of the nave. The obvious choice, therefore is that it should be Ham Hill stone as, at first glance the ashlar stonework has the same orange-brown colouring. However, Ham Hill Stone is a shell brash limestone whereas the stone supplied and used at the east end is an oolitic limestone. The stone actually used for the rebuilding was Doulting Stone, a Middle Jurassic stone in the Inferior Oolite group identified by its ooidal appearance when viewed under magnification. It often contains crinoid debris.

|

Trask and Sons Ltd took over the Doulting Quarries in 1889 and operated them under various company names until the 1930s. They advertised two types of Doulting stone Chelynch stone and Brambleditch stone as well as Ham Hill Stone (44). Both quarries are now filled in. The stone was used for the pillars (45a, 45b), archways and ashlar blocks lining the walls (see 43a).

|

References

1.Hill M., Newman J., Pevsner N. (2018), The Buildings of England, Dorset, Yale U. Press, p.116

2. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2 /pp104 -2323. Feacey, Jem,

3. The Sequence and Evolution of Architectural Styles in the Church of Fordington St.George, Dorchester, 30 164-195

4. R. G. Bartelot, The History of Fordington, 1915

1.Hill M., Newman J., Pevsner N. (2018), The Buildings of England, Dorset, Yale U. Press, p.116

2. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/dorset/vol2 /pp104 -2323. Feacey, Jem,

3. The Sequence and Evolution of Architectural Styles in the Church of Fordington St.George, Dorchester, 30 164-195

4. R. G. Bartelot, The History of Fordington, 1915